The following was published on Food Tank in December of 2023. You can read the original here. Contributing authors: Liza Greene, Elena Seeley, and Alessandra Uriarte

The food and agriculture movement made incredible strides over the last year—but our work isn’t done yet!

The ambition to transform food systems is demonstrated every day by networks building capacity for farmers and ranchers, organizations forming unusual partnerships to achieve shared goals, programs giving voice to youth, and initiatives investing in community-led innovations and solutions. These groups are continuing to push for food and agriculture systems that are economically, socially, and environmentally just and equitable. Food production and consumption that ensures everyone has access to healthy, affordable, culturally relevant, and delicious food. And they are calling on everyone to take part in their work!

As we head into the new year, here are 124 organizations to follow, engage with, and support in 2024.

1. Act4Food, International

A youth-led organization bringing youth from across the globe, Act4Food, Act4Change utilizes the power of youth to advocate for a sustainable food system. With a focus on personal actions and a set of prioritized Actions 4 Change, the campaign aims to influence governments and businesses to address food accessibility, climate change, and human rights.

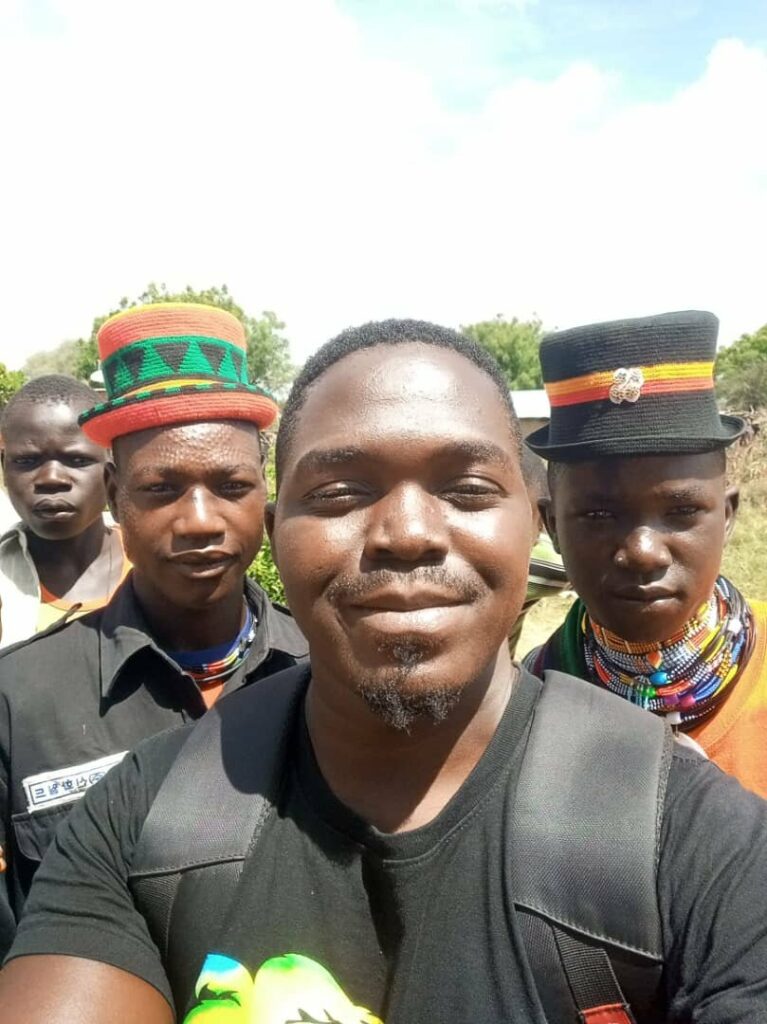

2. Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA), Africa

AFSA is an alliance uniting civil societies dedicated to promoting agroecology and food sovereignty across Africa. The Alliance is rooted in values for fair and inclusive development, harmonious coexistence with nature, and the empowerment of local communities. “[Social] cohesiveness is very critical when you’re attacked by a climate crisis,” says Million Belay, General Coordinator for AFSA. “You can mobilize together. You can help each other.”

3. Arrell Food Institute, Canada

The Arrell Food Institute focuses on addressing global food security challenges through research, innovation, and policy development. The Institute aims to advance sustainable and nutritious food production systems, improve food distribution and access, and contributes to policy discussions.

4. Asian Farmers Association for Sustainable Rural Development (AFA), Asia

AFA works to empower and strengthen the capacities of leaders and technical staff to increase resilience and combat hunger. They engage in policy advocacy, capacity building, knowledge management, and sustainability initiatives. And the organization recently partnered with organizations to host the Global Conference of Family Farmers for Climate Action in Italy.

5. Audubon Society, United States

Recognizing the link between food systems and wildlife conservation, the Audubon Society launched the Conservation Ranching Initiative. Ranchers that adhere to the program’s standards earn use of the Audubon Certified bird-friendly seal, a product label connecting consumers to conservation by confirming beef and/or bison products come from lands managed for birds and biodiversity.

6. Ayudando Latinos A Soñar, United States

Ayudando Latinos A Soñar is Latino-centered nonprofit in California that helps children and families feel pride in their identity. When record levels of precipitation triggered extreme floods that devastated agricultural communities, ALAS was among the first organizations to respond and help the region’s farm workers and their families.

7. Beans is How, International

Mobilized by the SDG2 Advocacy Hub, Beans is How is a campaign to highlight the importance of beans as an affordable and simple solution to health, environment, and financial challenges across the globe. Their goal is to double the global consumption of beans, peas, lentils, and other pulses by 2028.

8. Better Soil, Better Lives, Africa

Founded by Roland Bunch, Better Soils, Better Lives, has a goal to triple the productivity and mitigate droughts for at least 70 percent of the small-scale farmers in sub-Saharan Africa over the next 20 years. The organization introduces beneficial plants called green manure/cover crops which fertilize the soil, control weeds, and respond to periods of drought.

9. Black Urban Growers, United States

Black Urban Growers (BUGs) is dedicated to fostering a robust community that supports cultivators in urban and rural environments, while nurturing Black leadership. The organization’s 2023 Annual National Conference was held in Philadelphia, to connect, collaborate, and delve into the world of Black agriculture and food systems.

10. Black Dirt Farm Collective, United States

The Black Dirt Farm Collective is dedicated to mobilizing personal, cultural, and technical capacities of Black agrarian communities. The Collective works to bridge gaps among generations, advocate for socio-cultural education grounded in wisdom and nature, and empower historically marginalized individuals. They are a recipient of the 2023 Food Sovereignty Prize.

11. Blackwood Educational Land Institute, United States

This nonprofit teaching farm aims to inspire the next generation of farmers and ecologists. By promoting restorative agricultural practices and instilling a strong work ethic in youth, the Institute fosters awareness of the critical role regenerative food systems play in addressing environmental challenges.

12. Blue Food Assessment, International

The Blue Food Assessment is a joint initiative that brings together scientists from across the globe to support decision-makers to build equitable and sustainable blue food systems. They work to address gaps in understanding the roles of aquatic foods in the global food system, with a mission to educate and drive change in the policies and practices.

13. Bread for the World, United States

Bread for the World, a faith-based advocacy nonprofit, engages in partnership building and policy advocacy to try to address hunger in the U.S. and worldwide. The organization provides people with educational resources to help them advocate for policies and programs that will make it easier for those in need to access food. “I believe that no one wants children to go hungry. Nobody wants families to go hungry. Nobody wants farmers in urban and rural contexts to go hungry,” Reverend Eugene Cho, CEO and President of Bread for the World tells Food Tank.

14. CARE, International

CARE seeks to create an equitable world with hope, inclusivity, and social justice by working to improve basic education, increase access to quality healthcare and expand economic opportunity for women and girls across the globe. This year alone, the organization worked in 109 countries and reached 167 million women and girls from over 1,600 projects.

15. Centre d’Etude Régional pour l’Amélioration de l’Adaptation à la Sécheresse (CERAAS), Senegal

CERAAS works to improve quality of life in West and Central Africa and alleviate the negative impacts of drought and agricultural production to minimize food shortages. The organization’s goal is to increase farming productivity and economic growth by finding technologies and innovations suited to the climate and agricultural conditions of arid and semi-arid regions.

16. CGIAR, International

As the largest global agricultural innovation network, CGIAR is working to the transform food, land, and water systems. Operating as One CGIAR to take a cohesive, coordinated approach across all organizations in their network, they utilize research to drive science and innovation and tackle pressing global and regional challenges. Organizations under CGIAR include CIMMYT, which is focused on improved quantity, quality, and dependability of production systems and basic cereals. And The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT researches climate change, biodiversity loss, environmental degradation, and malnutrition.

17. Chef Ann Foundation, United States

The Chef Ann Foundation offers professional development and district support to assist school districts establish, execute, and maintain self-operated, cook-from-scratch programs. Their Get Schools Cooking offers grants to districts that want to transition to scratch cooked meals. To date, the Foundation has reached 3.4 million children and 14,000 schools.

18. Community Food Navigator, United States

The Community Food Navigator fosters collaboration and strengthens connections between food growers, producers, educators, and consumers through trust and wisdom. To achieve their goal and achieve food sovereignty for the local community, they leverage digital tools that connect food systems stakeholders.

19. Community Servings, United States

Community Servings is providing scratch-made medically tailored meals to support individuals and their families who experience critical or chronic illness and nutrition insecurity. They also work closely with clients to provide nutrition education, counseling, food service job training through local foods initiatives. David Waters, CEO of Community Servings recently joined Food Tank at the Advancing Food is Medicine Approaches Summit—watch here.

20. CORAF, Africa

CORAF (the West and Central African Council for Agricultural Research and Development) is Africa’s largest sub-regional research organization to address pressing food and nutrition needs in West and Central Africa. Their work focuses on enhancing capacity, scaling technologies, facilitating access to technology, and supporting knowledge sharing to design solutions for producers. They also promote gender equity, youth empowerment, and market access.

21. Crop Trust, International

Crop Trust is dedicated to conserving plant genetic resources to promote sustainable agriculture and support global food security. The organization promotes an economically efficient global system of gene banks to ensure and advocates for an efficient global gene bank system.

22. Culinary Institute of America (CIA), United States

As a premier culinary college, the CIA seeks to encourage the next generation of leaders in the hospitality industry. “Essentially what we do is we lead the restaurant industry in terms of sustainability, nutrition, and public health and big ideas and food all through a lens of empathy, humanity and flavor,” Rupa Bhattacharya, Executive Director of Strategic Initiatives and Industry Leadership at the CIA, tells Food Tank. The school seeks to understand and promote its relationship to health, the environment, and a vibrant, and an equitable economy.

23. DC Central Kitchen (DCCK), United States

DCCK works to combat hunger and poverty by providing culinary job training and creating living wage jobs for those facing employment barriers. The nonprofit operates social ventures, including serving scratch-cooked meals and increasing access to affordable produce — all rooted in values to build an equitable food system.

24. Decent Work for Equitable Food Systems Coalition, International

The International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and CARE International launched the Coalition to tackle poverty and inequality for food systems workers. Their work is focused on five priority areas: labor and human rights, employment creation, living wages, social protection, and social dialogue.

25. Demanda Colectiva, Mexico

The Demanda Colectiva has fought to protect Mexico’s native maize varieties, which are threatened by uncontrolled cross-pollination from genetically modified corn. This year, they were the recipient of the Pax Natura Foundation’s annual environmental prize.

26. EAT, International

EAT is a science-based organization focused on creating fair and sustainable food systems to keep the plant and everyone healthy. In collaboration with the Stockholm Resilience Centre, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Harvard University, and OneCGIAR, they launched the EAT-Lancet 2.0 on healthy diets and sustainable food systems. EAT-Lancet 2.0 will be launched in 2024.

27. Edible Schoolyard Project, United States

The Edible Schoolyard Project offers experiential learning, connecting students to one another, nature, and food while addressing the climate crisis and health inequities. Founded by Chef Alice Waters, the organization has helped establish thousands of gardens across the U.S. “The foods that the kids cook really empowers them,” Waters tells Food Tank. “And they are changed by it.” Waters is also a strong proponent of leveraging the power of institutional procurement to support sustainable agriculture practices and strengthen local communities.

28. Environmental Defense Fund, United States

The Environmental Defense Fund is guided by science, economics, and a commitment to climate justice, to make the largest impact. The organization strives to tackle the climate crisis through innovative solutions to stabilize the climate, strengthen people and nature’s ability to thrive, and support people’s health. Their food systems work includes efforts to support sustainable fisheries, promote climate-friendly agriculture practices, and advance research on soil health.

29. Fairtrade International, International

Co-owned by more than 1.8 million farmers and workers, Fairtrade is a global organization working to ensure fairer prices for producers and support environmental sustainability. The Fairtrade system is made up of three regional producer networks that represent farmers and workers along with more than 25 national Fairtrade and marketing organizations and an independent certifier.

30. FAIRR Initiative, International

The FAIRR Initiative is a global network of investors that raises awareness of the environmental challenges and opportunities in the food sector. They focus on providing research and coordinator policy action for their members so that investors can make informed decisions and unlock the resources needed for food systems transformation.

31. Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC), United States

FLOC empowers farm workers to have a voice in decisions that impact them. What began as a small group of farm workers in northwest Ohio has since grown to include thousands of workers around the country. The union educates farm workers on their labor rights, resolves grievances on farms, and creates community organizing committees.

32. Fed By Blue, United States

As a science-based communications initiative, Fed By Blue aims to transform blue food systems through empowerment, education, and policy and practice. In 2024, PBS will air Hope in the Water, a three part documentary series that is part of a larger impact campaign led by the organization. The series uncovers creative solutions that can protect threatened seas and fresh waterways while feeding future generations.

33. First Nations Development Institute, United States

The First Nations Development Institute works to empower Native economies and promotes economic development for individuals and communities. With diverse support, the institute focuses on financial empowerment, investment in youth, stewarding native lands, and fostering sustainable growth for Native Americans.

34. Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU), International

FOLU’s global community of change-makers strive to revolutionize the system by promoting equitable access to food, fostering social justice, and strive for a net-zero, nature-positive world. The organization relies on evidence and science-based solutions to empower farmers, policymakers, businesses, investors, and civil society in driving widespread change.

35. Food Chain Workers Alliance, United States & Canada

The Food Chain Workers Alliance is a coalition of labor-focused organizations working to improve working conditions and wages for those employed in the food chain. The Alliance advocates for fair compensation and recognition for all food workers, to ensure livable wages, promote cooperative ownership, and healthy and affordable food production.

36. Food Is Medicine Institute, United States

This year, the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University launched its Food is Medicine Institute. With a focus on Food is Medicine interventions, the Institute will serve as a catalyst to drive change, improve health, reduce health disparities, and establish a more equitable health system that prioritizes the power of food.

37. Food Recovery Network, United States

This collective of youth-led chapters engage college students in food recovery efforts. By redirecting surplus food to those in need, the organization strives to fight hunger, reduce food waste, and promote equity in food and agriculture systems. They operate on 179 campuses in 44 states and Washington D.C.

38. Food Systems for the Future, International

Food Systems for the Future envisions a world free of malnutrition where environmentally and economically sustainable food systems provide equitable access to affordable, nutritious food for all. Their work focuses on business acceleration, public policy and education, partnerships and community engagement, and investment capital. “It is essential to unlock the capital that is necessary for food systems transformation as well as the capital for a humanitarian response,” says Ertharin Cousin, President and CEO of Food Systems for the Future.

39. Forum For Farmers and Food Security (3FS), International

3FS is a global coalition dedicated to driving tangible action to transform food and agriculture systems. Together, we seek to improve global food and nutrition security while illuminating the inextricable link between food systems, both on land and sea, and climate resilience. “Let’s make sure the farmer is making money and living well,” Craig Cogut Founder, Chair, and CEO of Pegasus Capital—a partner of 3FS—tells Food Tank, “and then we can have nutritious, reliable food for all.”

40. Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR), United States

FFAR supports collaboration to advance scientific research that provides every person with access to affordable, nutritious food produced on thriving farms. The Foundation funds research on topics including soil health, urban food systems, and sustainable water management in agriculture. They also offer fellowship, grant, and award programs to invest in developing the future scientific workforce.

41. Future Economy Forum, International

Launched by NOW Partners, the Future Economy Forum is a global platform working to raise awareness and scale solutions to create a new economic mainstream. Working together with partners, they develop Solutions Initiatives, which model and scale solutions to address critical challenges. Some of these Initiatives help to scale regenerative agriculture and B Corp Certification.

42. Future Food Institute, International

The Future Food Institute sees food as the primary form of cultural expression and a catalyst for change. The Institute has identified themes that must be to create prosperous food systems. These include circular systems, water safety and security, climate, nutrition security, and sustainable cities. At COP28, Sara Roversi, Director of the Future Food Institute joined Food Tank for a conversation on healthy and sustainable diets. Watch here.

43. Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), International

GAIN works to advance nutrition outcomes by improving the consumption of nutritious and safe food for all. They are one of the organizations behind the Initiative on Nutrition and Climate Change (I-CAN), which aims to accelerate transformative action at the intersection of climate and nutrition. During COP28, I-CAN released a baseline report to track solutions that integrate climate and nutrition.

44. Global Alliance for the Future of Food, International

By uniting philanthropic foundations, the Global Alliance for the Future of Food looks to build food systems that are renewable, resilient, equitable, healthy, and diverse. During COP28, the Global Alliance and their partners launched a toolkit to help countries translate global commitments into ambitious local action. “We’ve turned a page on climate denial. Now we must be careful not to submit to climate doomism and climate dithering,” says Anna Lappé, the organization’s Executive Director.

45. Global FoodBanking Network (GFN), International

Active in more than 50 countries, GFN uses food banking to nourish eaters and contribute to a world free of hunger. By supporting the capacity of food banks, they also work to reduce food loss and waste and strengthen the resilience of communities.

46. Global Seafood Alliance, United States

The Global Seafood Alliance is the nonprofit behind two certifications helping consumers choose more sustainable seafood: Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) and Best Seafood Practices (BSP). They also engage in advocacy and education to advance better seafood production practices and host the annual Responsible Seafood Summit.

47. GRACE Communications Foundation, United States

GRACE Communications Foundation aims to advance solutions to the greatest challenges in the food, environment, and public health sectors. GRACE is behind FoodPrint, a project that raises awareness of food systems issues through reports and other resources. One of FoodPrint’s latest publications looks at the impact of forever chemicals on food systems.

48. GRAIN, International

Working across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, GRAIN supports small farmers and social movements trying to achieve community-controlled food systems that prioritize biodiversity. Their programs aim to deepen public understanding of the forces shaping food systems by focusing on corporate control, land grabs, people’s control of seeds, and food sovereignty as a solution to the climate crisis.

49. Green Bronx Machine, United States

Green Bronx Machine offers health, cooking, culinary, and gardening programs to foster students’ interest in STEM, address food insecurity, support workforce development, and inspire healthy living. The nonprofit has partnered with EXPLR to support the 2024 National STEM Challenge, which will celebrate student-developed innovations that bring positive change to communities.

50. GrowNYC, United States

Through farmers markets, waste collection sites, educational programs, and more, GrowNYC aims to help New Yorkers lead healthier lives. They operate more than 50 farmers markets and 16 farm stands across New York City’s five boroughs. Earlier this year, GrowNYC workers successfully formed a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.

51. Gwassi Integrated Farmers Advocacy, Kenya

Working in Homa Bay County in Kenya, the Gwassi Integrated Farmers Advocacy works to improve agricultural practices for improved food security and nutrition. The organization focuses on community organizing and grassroots advocacy, with an emphasis on youth involvement to support the next generation of farmers.

52. Harlem Grown, United States

Harlem Grown brings hands-on education in urban farming, sustainability, and nutrition to youth. The nonprofit is working to inspire the next generation to lead healthy lives. They currently have 13 urban agricultural facilities, school gardens, hydroponic greenhouses, and soil-based farms.

53. HEAL Food Alliance, United States

HEAL Food Alliance is a coalition of 55 multi-sector organizations working to build a more sustainable and equitable food system. They strive to build collective power that supports food producers while protecting the air, water, and land that everyone depends on. The organization recently released a report to advocate for value-based food purchasing to challenge corporate control in institutional procurement.

54. Healthy Schools Campaign, United States

The Healthy Schools Campaign develops program and policy recommendations that support healthy schools at the local, state, and national level. They also offer support to parents, students, and school staff and administrators to develop their leadership skills and help them advocate for health and wellness in the education sector.

55. Heifer International, International

By supporting and investing alongside local farmers and their communities, Heifer International is working to end hunger and poverty. Through the development of local partnerships, the organization supports farmer trainings that contribute to economic empowerment, particularly among women producers.

56. Heirloom Collard Project, United States

The Heirloom Collard Project is bringing attention to collards to ensure that they receive the recognition and respect as an important component of U.S. food culture. The researchers, farmers, chefs, artists, gardeners, and seed savers who contribute to the project work to preserve the seeds and stories of dozens of collard varieties.

57. IndigeHub, United States

Chef Bleu Adams founded IndigeHub to help Indigenous communities develop self-sufficiency and long-term success. “We thrive when we’re in balance, the Earth thrives when she’s in balance,” Adams tells Food Tank. “And that’s what we need to strive for.” To achieve this goal, the organization focuses on farmers and producers to address food insecurity and reintroduce Indigenous crops.

58. Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), Americas

IICA works to encourage, promote, and support their 34 Member States achieve agricultural development and rural wellbeing. During COP28, the agency facilitated the Sustainable Agriculture of the Americas Pavilion, which featured conversations with food systems leaders including U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, Mexico’s Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development Manuel Villalobos Arámbula, and Secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture Karen Ross.

59. International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE), Kenya

ICIPE conducts research on insects and other arthropods to develop and communicate affordable, accessible solutions to tackle crop pests and disease. At the start of 2024, Dr. Abdou Tenkouano, formerly the Executive Director of CORAF, will become the organization’s new Director General.

60. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), International

The research center of CGIAR, IFPRI focuses on providing research-based policy solutions to address poverty, hunger, and malnutrition. Their work encompasses five research areas: a climate-resilient and sustainable food supply, healthy diets and nutrition for all, inclusive and efficient markets and trade systems, the transformation of agricultural and rural economies, and strengthening institutions and governance.

61. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), International

To address the widening gap between the rich and the poor, the specialized U.N. agency IFAD supports rural communities’ efforts to increase their food and nutrition security and their incomes. The organization recently helped launch the Decent Work for Equitable Food Systems Coalition to tackle poverty and inequality for food systems workers.

62. International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), International

IPES-Food brings together an international group of researchers to inform the debate on global food systems reform. Recent reports from organization cover the relationship between the debt crisis and global food insecurity and the ways local governments are tackling the climate crisis through food. “Local governments…offer a blueprint for real people-centered climate action,” writes Nicole Pita, a Project Manager for IPES-Food.

63. James Beard Foundation (JBF), United States

JBF works to celebrate American food culture while pushing for new and better standards in the restaurant industry. They help chefs engage in policy advocacy around issues they are passionate about through opportunities including their Chef Bootcamp for Policy and Change and lobby days. JBF also celebrates achievements in the culinary arts, hospitality, media, and broader food system through their restaurant and chef, media, and leadership awards.

64. Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, United States

Operating out of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the Center for a Livable Future is working to transform food systems and protect public health. Their work tackles a range of food systems issues including food equity, animal agriculture, urbanization, food waste, seafood, and healthy and sustainable diets. They also conduct research and outreach to reduce the negative impact of food systems on the environment and support climate resilience and adaptation strategies.

65. K’allam’p, Ecuador

By offering support to Indigenous communities, K’allam’p is working to inspire resilient food systems while strengthening the sovereignty of the Andean people of Ecuador. Their goal of K’allam’p is to spread its regenerative framework, and the sovereignty that follows, across the Andes region and beyond.

66. Kitchen Connection Alliance, International

The Kitchen Connection Alliance engages youth as protagonists of food systems change through advocacy, events, and educational resources. They aim to empower eaters and help them contribute to a better food empowerment. To educate young readers about the food system, they are planning the release of a new children’s book. The Alliance’s Director Earlene Cruz recently joined Food Tank at the Food and Agriculture as a Solution to the Climate Crisis Summit, held during NYC Climate Week—watch here.

67. La Via Campesina, International

Composed of more than 180 organizations across 80 countries, the international peasant movement La Via Campesina advocates for food sovereignty, environmental justice, and peasants’ rights. “If people don’t control the food, they don’t control the power,” Morgan Ody, the General Coordinator for La Via Campesina, tells Food Tank. This year, they officially expanded into the Arab and North Africa region, establishing the organization’s 10th region.

68. MAZON: A Jewish Response to Hunger, United States

MAZON is an anti-hunger organization guided by Jewish values and ideals. They tackle food insecurity through policy advocacy, community engagement, community response fund, and strategic partnerships. In 2023, they launched their virtual Hunger Museum, which explores the history of food insecurity in the U.S. to inspire hope for a hunger-free future.

69. Milken Institute’s Feeding Change Program, United States

Feeding Change brings together food systems experts within the Milken Institute to build more nutritious, sustainable, resilient, and equitable food systems. Their Food Is Medicine Task Force aims to integrate food is medicine interventions into policy and finance to support nutrition security.

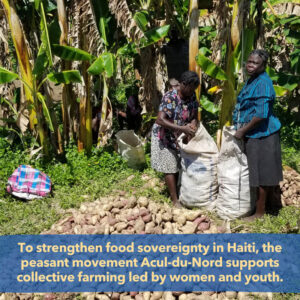

70. Mouvman Peyizan Papay (MPP), Haiti

With approximately 60,000 members, MPP is the largest peasant movement in Haiti. The grassroots organization advocates for the rights and interests of the country’s peasant farmers and rural communities. They are a recipient of the 2023 Food Sovereignty Prize.

71. Movement for Community-led Development in Liberia, Liberia

The Liberia chapter of the Movement for Community-led Development (MCLD) launched in 2020 to develop home-grown solutions to the country’s most pressing challenges. Through land redistribution and training programs, they are working to strengthen community bonds and increase producers’ collective power.

72. Muloma Heritage Center, United States

The Muloma Heritage Center is being developed to honor the past, present, and future of African Atlantic culture, cuisine, and traditions on St. Helena Island in the South Carolina Lowcountry. The project was co-founded by a group of chefs, agriculture experts, and artists including Adrian Lipscombe, Michael Twitty, and Tonya and David Thomas. Through the Center, the founders hope to make St. Helena an eco-tourism destination that can promote African Atlantic culture worldwide.

73. National Black Food and Justice Alliance (NBFJA), United States

A coalition of Black-led organizations, NBFJA is dedicated to developing Black leadership, supporting Black communities, organizing for Black self-determination, and creating the infrastructure needed for Black food sovereignty and liberation. Their work focuses on self-determining food economies, land, and Black food sovereignty.

74. National Young Farmers Coalition, United States

The National Young Farmers Coalition is working to shift power and change policies to empower the next generation of farmers. Their work addresses issues including land access, mental health, student loan debt, immigration and labor, and the climate crisis. Through their One Million Acres for the Future Campaign, they are calling on Congress to make a historic investment in the equitable access of 1 million acres of land for the next generation of farmers.

75. Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), International

NRDC works to defend all life on Earth and the natural systems that support it. As part of their food systems work, they engage in advocacy to stop food loss and waste. They also launched the Chefs for Healthy Soils Program, an initiative that engages chefs to raise awareness of the link between soil health and resilient food systems. “Chefs are a compelling voice who can use their influence for good by advocating for policies that promote soil health,” Lara Bryant Deputy Director of Water and Agriculture for NRDC tells Food Tank.

76. Niman Ranch Next Generation Foundation, United States

Niman Ranch established the Niman Ranch Next Generation Foundation to help the children of farmers and ranchers continue their education. The Foundation has provided almost US$500,000 in grants to farmers like Aaron Williams, a sixth generation pig farmer.

77. North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NATIFS), North America

Chef Sean Sherman, the 2023 recipient of the Julia Child Award, created NATIFS to re-establish Native foodways and address the economic and health crises affecting Native communities. The organization recently established the Indigenous Food Lab, a professional Indigenous kitchen and training center, which also runs the Indigenous Food Lab Market.

78. One Fair Wage, United States

One Fair Wage works to eliminate sub-minimum wages across the United States and improve the working conditions for workers in the private sector. With their 25 by 250 Campaign, the organization is advocating for legislation and ballot measures in 25 states that will raise wages for millions of workers by 2026, which marks the 250th anniversary for the U.S.

79. Participant Media, United States

Participant Media is behind Oscar-nominated and Emmy-award winning documentary Food, Inc. and its sequel Food, Inc. 2. The films underscore the influence of corporations on the U.S. food system and the innovative leaders pushing for a more sustainable, equitable, resilient food future. Participant also helps eaters inspired by the films get involved through calls to action.

80. Planet Forward, United States

Planet Forward is a project of the Center for Innovative Media at the George Washington University School of Media and Public Affairs. Because they believe that environmental and science communication is needed now more than ever, they teach and celebrate environmental storytelling by college students.

81. Practical Farmers of Iowa (PFI), United States

By cultivating a network of producers across the state of Iowa, PFI is working to build resilient farms and communities. They support farmer-led research and education, offer personalized assistance to help farmers reach their goals, and conduct outreach to raise awareness to diversify the state’s agriculture system.

82. Project Bread, United States

Project Bread is on a mission to end hunger in Massachusetts through a combination of advocacy and programmatic work. Thanks to the advocacy work of Project Bread and their partners, Massachusetts became the 8th state in the U.S. to implement permanent universal free school meals.

83. Project Drawdown, United States

Project Drawdown aims to help the world stop and reverse the effects of the climate crisis as quickly, safely, and equitably as possible. They do this using three key strategies: advancing effective and science-based climate solutions; fostering bold, new climate leadership; and promoting new narratives to promote stories of possibility and opportunity.

84. ProVeg International, International

By 2040, ProVeg International wants to reduce the consumption of animal products globally by 50 percent. They hope to do this through awareness campaigns that will help consumers understand the impact of their dietary choices on the environment and embrace plant-based protein alternatives to meat and dairy products.

85. ReFED, United States

ReFED uses data-driven solutions to help end food loss and waste in the U.S. In the last year, the organization updated their Insights Engine, a tool that provides insight into the latest data on food loss and waste in the country as well as a database of solutions.

86. Regen10, International

Guided by 10 core principles that aim to center farmers, equity, and inclusion, Regen10 was established to create regenerative global food systems. They believe the most effective way to scale regenerative food systems is to build evidence and create a shared understanding of how to deliver positive outcomes in different contexts.

87. Regenerate America, United States

Launched by Kiss the Ground, Regenerate America is a coalition of farmers, businesses, and nonprofits working to include more resources for regenerative agriculture in the next Farm Bill. Through the widespread adoption of these practices, they believe it’s possible to improve food and water security while strengthening climate resilience.

88. Teens for Food Justice (TFFJ), United States

For 10 years, TFFJ has used school-based hydroponic farming to reduce hunger, improve nutrition education, and engage youth in New York City. Working in 19 schools, they distribute more than 20,000 kilograms of student-grown produce and offer more than 97,000 servings of leafy green vegetables.

89. Rainforest Alliance, International

The Rainforest Alliance works at the intersection of business, agriculture, and forests to create a new standard for business operations. They work with companies along the agricultural, food, and forestry supply chains, helping them implement practices that are better for workers and the planet. Their Rainforest Alliance seal signifies that certified ingredients were produced in a way that supports social, economic, and environmental sustainability.

90. Rodale Institute, United States

Since 1947, the Rodale Institute has led research on regenerative organic agriculture. Together with Dr. Bronner’s and Patagonia, they launched the Regenerative Organic Certification, a new certification program that encompasses soil health, animal welfare, and workers’ wellbeing.

91. Rural Mental Health Outreach Program, United States

Created by Ted Matthews, the Rural Mental Health Outreach Program provides mental health services to farmers, ranchers, and farming families in Minnesota to help them grapple with the unique pressures and challenges of the agriculture sector. The services are offered at no cost to producers thanks to funding from the state.

92. Rythu Sadhikara Samstha (RySS), India

RySS is an organization developed to build farmers’ empowerment in India. They are implementing Andra Pradesh Community Managed Natural Farming (APCNF), a training program that helps producers farm in harmony with nature. Hear from Vijay Kumar, Executive Vice-Chairman of Ryss at COP28 here.

93. Senegalese Association for the Promotion of Development at the Base (ASPRODEB), Senegal

ASPRODEB is an association of farmers and fishers working to strengthen food systems across West and Central Africa. They help to facilitate farmer-to-farmer sharing and connect producers with agricultural innovations. “Farmers are knowledge producers,” Ousmane Ndiaye, Director of ASPRODEB tells Food Tank. “Not only doctors have knowledge.”

94. Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement, International

Since 2010, the SUN movement has worked to end malnutrition in all its forms. They unite stakeholders from across the food system including civil society, U.N. entities, the donor and philanthropic communities, businesses, and researchers to achieve this goal by 2030.

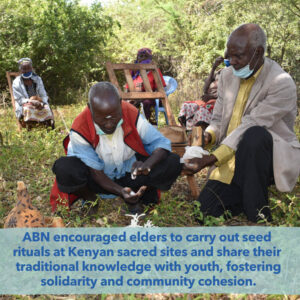

95. Seed Savers Network, Kenya

Seed Savers Network Kenya is working to strengthen communities’ seed systems to conserve agrobiodiversity and improve food sovereignty. The organization operates their Farmer Training Centre and community seed banks. They also promote equity for women farmers through gender mainstreaming and advocate for farmers’ rights by amplifying their needs.

96. Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), India

Established in 1972, SEWA unites 2.5 million self-employed women workers in the informal economy. The Association recognizes the essential role its members play as food producers, distributors, vendors, cooks, and caregivers, and seeks to transform food and agriculture systems to increase their collective strength.

97. Sicangu Food Sovereignty Initiative (SFSI), United States

The Siċaŋġu Food Sovereignty Initiative is a community-based effort to indigenize the food system. Their core projects include a community garden, farmers market, and local food subscription program, which support food security; an internship program to introduce youth to local food production; and community events that center the preservation of traditional Lakota food knowledge and practices.

98. Slow Food International, International and Slow Food USA, United States

Slow Food is a global movement that is advocating for everyone to have access to high quality, sustainably produced food. Through their work, they try to defend biological and cultural diversity, educate and inspire eaters, influence policies and programs to support food systems transformation, and develop Slow Food’s network. Slow Food USA is the national movement in the U.S. working to advance the Slow Food mission.

99. SMART Training Platform, Canada

The SMART Training Platform emerged as a collaborative project that is engaging student researchers who want to build more resilient food systems. The Platform focuses on the implementation of the scientific method and allows students to create scalable solutions to real world challenges including food insecurity and food waste.

100. Sociedad de Historia Natural Niparajà, Mexico

Sociedad de Historia Natural Niparajà is a conservation organization that has worked for more than 30 years to preserve water resources. Their Marine Conservation Program works with a variety of stakeholders to manage and protect marine ecosystems. And their Sustainable Fishing program works closely to develop sustainable fisheries.

101. Solidaridad, International

Solidaridad is a civil society organization working to create fair and sustainable supply chains to make sustainability the norm, not the exception. Their Small Farmer Atlas is a new report informed by interviews with small-scale farmers in 18 countries, which looks at issues including prosperity and income, bargaining power, and land use.

102. Soul Fire Farm, United States

Soul Fire Farm is an Afro-Indigenous centered community farm that strives to uproot racism and establish sovereignty in the food system. They offer educational programs and distribute fresh produce to end food apartheid. This year, Soul Fire Farm’s Co-Founder Leah Penniman released her second book Black Earth Wisdom, a collection of essays and interviews that explores Black people’s spiritual and scientific connection to the land.

103. Sustainable Food Trust, United Kingdom

The Sustainable Food Trust aims to create the necessary policy, economic, and cultural environment to accelerate food systems transformation. Their key focus areas include True Cost Accounting, sustainable livestock, food security in Britain, antibiotic use in the animal agriculture sector, measuring sustainability, and local food systems.

104. Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems at Arizona State University, United States

At Arizona State University, the Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems is working to drive social progress, economic productivity, and ecosystem resilience through food systems transformation. They advance organic research and policy, enable True Cost Accounting, educate the next generation of food systems leaders, and engage the private sector.

105. The Nature Conservancy (TNC), International

TNC is an environmental organization working around the world to create a world where all life thrives. To help feed the world sustainably, their goal is to conserve 10 billion acres of ocean, 1.6 billion acres of land, and 620,000 miles of rivers. As part of their work on aquatic ecosystems, TNC partnered with shellfish farmers to create the Shellfish Growers Climate Coalition to help producers take climate action.

106. The Rockefeller Foundation, United States

The Rockefeller Foundation is working to advance more regenerative, nourishing, and equitable food and agriculture systems. The Foundation’s food systems work includes initiatives focused on school meals, food is medicine, procurement, and regenerative agriculture. And through their Periodic Table of Food Initiative, they are building a global ecosystem and providing tools, data, and training to catalog the biomolecular composition of the world’s food supply. In 2023, they co-hosted Pre-COP Food Day at the U.N. General Assembly to build momentum around food systems in the leadup to COP28.

107. Ujamaa Cooperative Farming Alliance (UCFA), United States

UCFA is a collective of new and established growers who cultivate and distribute heirloom seeds and grow culturally meaningful crops. Through this work, they hope to provide more opportunities and support for growers from historically oppressed and marginalized communities. To support their efforts, they also sell seeds through their business, Ujamaa Seeds. “Seeds are living things,” Ira Wallace, a seed saver and advisor to Ujamaa tells Food Tank. “You can’t just put them away.”

108. U.N. Development Programme (UNDP), International

UNDP works in 170 countries and territories to eradicate poverty and reduce inequality. They work with countries to develop policies, leadership skills, partnering abilities, and more. They operate 10 programs and initiatives dedicated to supporting the transformation of food and agricultural commodity systems, which they believe is essential to sustainable development.

109. U.N. Environment Programme (UNEP), International

UNEP aims to inspire, inform, and enable people to improve their quality of life and conserve natural resources for future generations. Their work encompasses a range of issues including oceans and seas, forests, youth and education, and gender. UNEP’s food systems work includes efforts to address food loss and waste and support for farmers through strategic partnerships.

110. U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International

Working in more than 130 countries, FAO is the specialized agency of the U.N. that leads international efforts to end hunger and improve food and agriculture systems worldwide. During COP28, the FAO launched the first part of its Global Roadmap, which outlines a path for investors and policymakers to reduce the negative environmental impact of food and agriculture systems.

111. U.N. Global Compact, International and U.N. Global Compact Norway, Norway

The U.N. Global Compact is a voluntary initiative based on CEO commitments to implement universal sustainability principles. They work with the private sector to achieve the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, including those to end hunger, promote sustainable consumption and production, and protect aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. The U.N. Global Compact Norway is one of the country-level, local networks that has seen the greatest growth. This network is tackling solutions focused a range of issues including health and sustainable food systems.

112. U.N. World Food Programme, International

The U.N. World Food Programme (WFP) is the world’s largest humanitarian organization, has a presence in more than 120 countries and territories to bring food to those in need. Their work encompasses a range of focus areas from emergency relief and nutrition to climate action and resilience building.

113. Urban Growers Collective, United States

Urban Growers Collective works in Chicago, Illinois to build a more just and equitable local food system. Through urban agriculture, they aim to address the inequalities that persist in food and agriculture systems. “You can’t unpack food justice without addressing structural racism, historic inequities,” says Erika Allen, Urban Growers Collective’s Co-Founder & CEO – Strategic Development and Programs.

114. U.S. Hunger, United States

U.S. Hunger is a hunger relief organization that is leveraging the power of technology to connect people in need to healthy, nutritious food by delivering it to their front door. The organization’s CEO recently joined Food Tank at the “Advancing Food as Medicine Approaches” Summit to discuss the importance of both qualitative and quantitative data in solving the hunger crisis.

115. US Food Sovereignty Alliance, United States

The U.S. Food Sovereignty Alliance brings together organizations across the United States that are pushing for food sovereignty. Every year, they award the Food Sovereignty Prize, which recognizes two grassroots organizations dedicated to advancing food sovereignty and justice. The 2023 Prize went to Black Dirt Farm Collective and Mouvman Peyizan Papay (MPP).

116. Volgenau Climate Initiative (VCI), United States

VCI is a leadership program dedicated to accelerating nature-based climate action. They convene small groups for retreats designed to bring people together in natural settings, develop strong networks, and encourage new ways of thinking. Events topics have included diet and climate, land stewardship, and scaling diversified regenerative agriculture.

117. Wholesome Wave, United States

Wholesome Wave is an organization that strives to address diet-related diseases by helping low-income Americans buy and eat healthy fruits and vegetables. The organization recently launched the for-profit brand Wholesome Crave to provide plant-based meal solutions to large scale dining facilities and bring in revenue that can support Wholesome Wave’s work.

118. Women Advancing Nutrition Dietetics and Agriculture (WANDA), United States

Founded by Tambra Raye Stevenson, WANDA is working to achieve nutrition equity in the U.S.by uplifting the voices of Black women and girls in food. The organization recently conducted the Black Food Census to collect better data on Black foodways in the country. Stevenson hopes the data will inform positive changes in the U.S. food system.

119. Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty, Canada

The Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty (WGIFS) works to increase awareness and mobilize communities around Indigenous food sovereignty. The WFIGS organizes regular meetings and discussions and facilitates capacity building within communities. “To have sustainable food and sustainable water means having a sustainable world for all of us to coexist with each other,” says Lisa Kenoras, Communications Coordinator for the WGIFS.

120. World Central Kitchen (WCK), International

World Central Kitchen (WCK) provides chef-prepared fresh meals to people around the world affected by humanitarian, climate, and community crises. In recent months, WCK has worked in dozens of areas including in Mexico, the state of Tennessee, Gaza, Israel, Lebanon, and Ukraine. The recent film “We Feed People” documents the work of WCK’s Founder, Chef José Andrés.

121. World Farmers Market Coalition, International

Since launching in 2021, the World Farmers Market Coalition has grown to represent more than 20,000 markets and 60 associations from more than 50 countries to highlight the role of farmers markets in sustainable food systems. This past year, they held their first General Assembly of the World Farmers Market Coalition in Rome.

122. World Resources Institute, International

A global nonprofit, the World Resources Institute (WRI) uses research-based approaches and coalitions to protect and restore nature and stabilize the climate. Their food systems initiatives include projects on climate-friendly diets and food loss and waste. At COP28, WRI’s work was featured in several panels on food waste.

123. World Wildlife Fund (WWF), International

WWF works to conserve the Earth’s natural resources and help people around the world make more climate-friendly decisions. They advocate for eaters everywhere to reconsider food and agriculture systems to produce enough to feed the growing population in a sustainable way. WWF recently released a new framework to drive food systems transformation forward.

124. WorldFish, International

WorldFish is a research and innovation organization focusing on the role that aquatic foods play in supporting the livelihoods and wellbeing of millions of women, men, and children. They produce evidence-based solutions that target six intersecting themes: nutrition, gender, climate, sustainability, economy, and COVID-19.

Photo courtesy of Michael Pfister, Unsplash