In February 2020, the first Slow Food Academy on Agroecology welcomed participants from four different East and Central African countries (Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Democratic Republic of Congo). The initiative aims to train young producers and farmers in agroecology, with the goal of spreading agroecological practices and restoring value to local biodiversity through different field projects, such as the Slow Food Gardens in Africa. One of the Academy’s recent graduates, Ochen Umar Bashir, shared photos and his experience of the program with the Agroecology Fund.

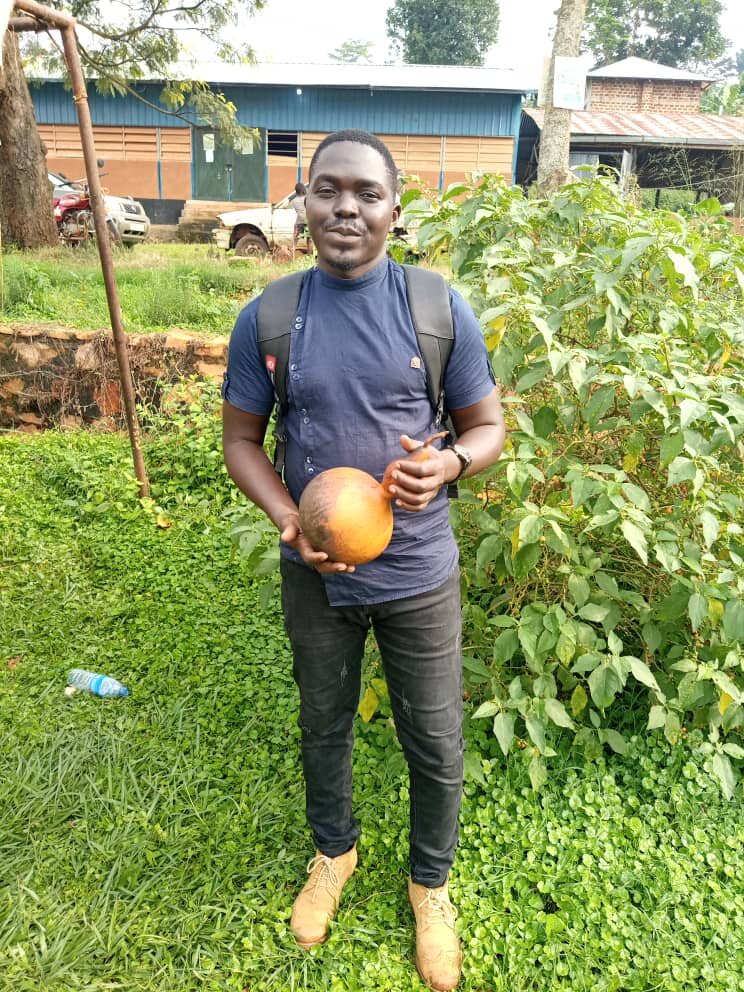

Ochen Umar Bashir (in the above picture), 31, participated in the Slow Food Youth Academy, a six-month program during which youth (aged 18-35) from different regions of Africa had the opportunity to learn more about agroecology and its impacts. Among the trainees were young farmers and agronomists, Indigenous peoples, agricultural officers and teachers, journalists and academic students. During their time together, students shared their diverse farming experiences and agricultural practices with each other, unique to the ecosystems they call home. “I liked that there was a lot of experience sharing about the way we do different things in different regions.”

Bashir, who is an agronomist by profession, joined the program to learn more about agroecology and how to better protect biodiversity through farming practices. “When we farm we should consider future generations and our surrounding areas. If we are to continue the same way without minding the environment, things will not be good.”

“Many of us studied agriculture in school and university but we realized that what we studied was misleading. The government supplies seeds to farmers for planting, but they don’t correlate with our current climatic conditions. We suffer prolonged dry spells, and rain is uncertain” said Bashir.

“Industrial agriculture has made farmers dependent on outside supplies, and minimized the processes they can have control over. Fertilizers, pesticides, seeds — we are in an era where business has taken over everything.”

“When I got to know about agroecology I was very interested in learning how it can lead to a reduction in food insecurity in my region, and to understand more about sustainable farming even in drought conditions.”

The program was as much about unlearning as it was about learning. “Farmers were taught that one crop planted in a very clean field was the correct way. Everyone would be spraying pesticides that affect the soil. Now, we learn that we must encourage mixed cropping, and the growing of trees. There is a relationship between biodiversity and farming.”

“It is important for youth to be interested in agroecology. Youth are the future generation and they are the ones who have to face the challenges ahead. They are strong and if they embrace agroecology, they will help it spread” explained Bashir. “Our elders would practice these traditional methods of agriculture which protected the soil and the water. But the challenge is they did not pass their knowledge to the youth. Or maybe the youth wanted a modern life! But now we need to take that knowledge and spread it further.”

“As a result of drought, pest outbreaks, and Covid-19, there is growing awareness that we should learn how to diversify and survive on local seeds. We are returning to our staples like sorghum; local varieties will grow even during a dry spell.”

After the program, Bashir formed an Indigenous Youth Network on Facebook where young farmers share their successes and challenges in practicing agroecology. He has also formed a group of 30 trainers who will establish demo Slow Food gardens and offer technical support to those in their community who are transitioning to agroecology.

Still, there is much more to be done. The youth from the Academy engage with local leaders and agriculture officials at community forums, and discuss with them the effects of pesticide use and so-called “improved” seeds from other regions. “Commercial farming is what is promoted, which promotes productivity at the expense of the environment”. With positive influence from above, Bashir feels many more community members will appreciate the concepts of agroecology and be convinced about its benefits.

The Slow Food Youth Academy was developed within the framework of the project “Building Local Economies in Eastern Africa through Agroecology” supported by the Agroecology Fund. The project will continue to establish new Slow Food gardens in the schools and communities of the four East African countries (Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo), encouraging youth involvement, livelihoods, and food sovereignty through agroeocology.