Photographs by Camila Falquez

Text by Isvett Verde

The following article was published in The New York Times in October of 2022. You can read the original here.

The natural resources that Indigenous peoples depend on are inextricably linked to their identities, cultures and livelihoods. Even relatively small changes in temperature or rainfall can make their lands more susceptible to rising sea levels, droughts and forest fires. As the climate crisis escalates, activists fighting to protect what remain of the world’s forests are at risk of being persecuted by their governments — and even at risk of death.

For decades Indigenous activists have been sounding the alarm. But their warnings have too often been ignored. So, they organized.

Indigenous peoples and communities, working in the Americas, Indonesia and Africa joined forces and together became the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities. They work to protect their rights and territories, amounting to nearly 3.5 million square miles of land across the planet.

“For us, the plants, the trees have life, they have a spirit, that’s why we have to respect it, take care of it and protect it. The women in my community have planted trees, bananas, cassava. We are dressing Mother Earth.”

— Briceida Iglesias, the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests, Panama

“Guna Yala is where we come from. It is not just a territory; it is more than that. It is a community — a family. ‘You are the next generation,’ my father told me. ‘And you must fight for your future.’ That gave me the drive to finish college and return to work for my community.”

— Yaily Castillo, the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests, Panama.

“Everyone agrees on the conservation of nature, on fighting climate change. But in practice they say that where you put the money you put the heart, and governments are not putting the heart. We want to be seen as partners in this fight.”

— Gustavo Sánchez, the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests, Mexico.

“Our spiritual, ritualistic and cultural practices are closely linked to the flow of nature. We use the rivers as a means of transport, but the rains have become scarce, isolating many communities. Several species — flora and fauna — are disappearing, which has led to a shortage of food and has limited our ability to perform certain rituals. This has had a dramatic impact on our culture. The cause is partly climate change, but these changes can also be linked to our government’s dismantling of environmental policy.”

— Dinamam Tuxá, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, Brazil.

“The oil that comes out of the Amazon, the gold — these natural resources feed development models, but we are left with garbage, oil pollution and mercury in the rivers. It is very sad that the United Nations only speaks to the presidents because their governments do not listen to us. The voice of the people must be respected. I call on the world to join our fight.”

— Gregorio Mirabal, Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin, Venezuela.

Working across multiple languages and political and legal systems, the alliance settled on five priorities: land rights, free prior and informed consent before any intervention into their territories, direct access to climate funding, protection of people from violence and prosecution, and the recognition of traditional knowledge in the fight to defend the planet.

In September, members of the alliance and their allies visited New York to meet with policymakers and donors during Climate Week, which brings together international leaders to push for global climate action.

They harnessed the power of speaking as a united voice, describing promises made by governments and international bodies that have failed to materialize into action. They explained how even though money to fight climate change so often doesn’t reach them, they have managed to develop programs that are helping communities mitigate and adapt to a changing climate. Imagine what could be possible with more funding and support.

“We have no more land to put our animals, to grow our medicinal plants. We want our trees back. We want to give our children our own medicine. We are part of the solution. We have our local knowledge, and we have ancestral knowledge. Give us a chance to bring our knowledge to the table.”

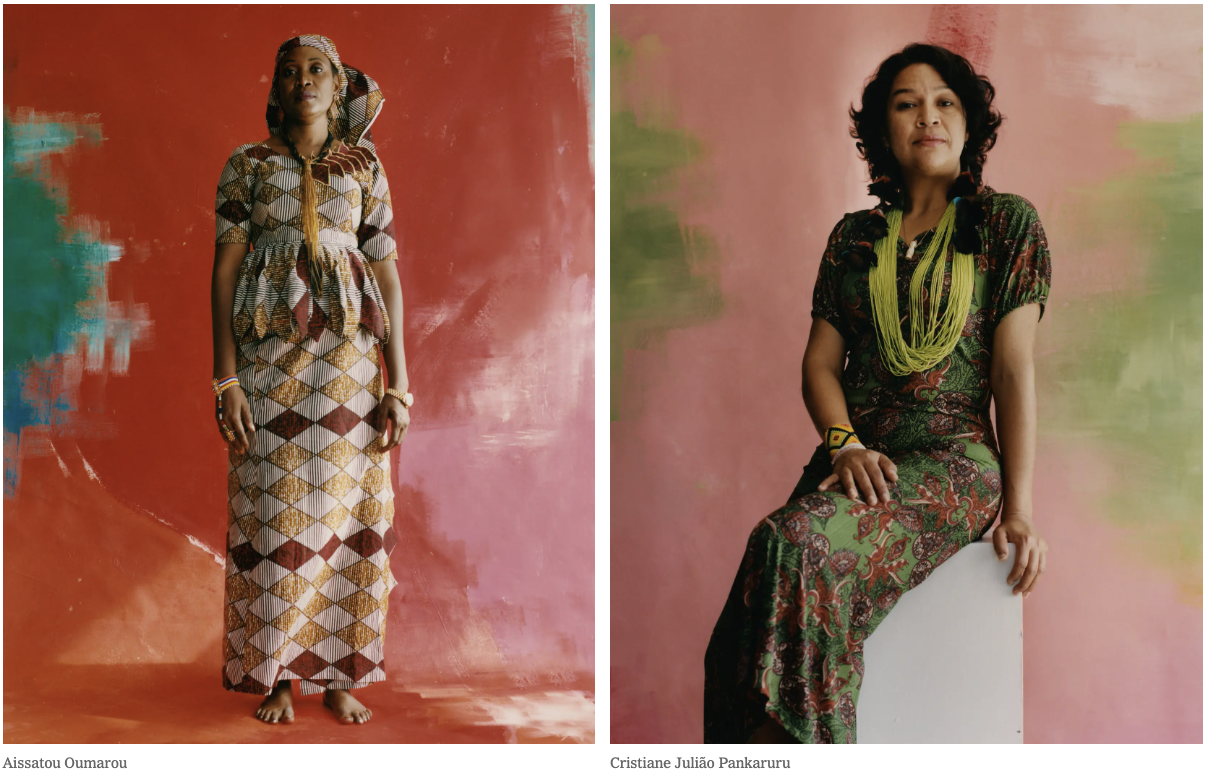

— Aissatou Oumarou, the Network of Indigenous and Local Populations for the Sustainable Management of Forest Ecosystems in Central Africa, Chad.

“Hope always needs to be nurtured. Everything is a process and, like any slow process, it has its time. Just as things in nature also have their time. And we only ask the creator for strength to give us wisdom, discernment. But we don’t feed on hope. So day after day, we fight.”

— Cristiane Julião Pankaruru, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, Brazil.

“My community and territory has already been destroyed by palm oil plantations. There is only a very small forest left. The loss of the territory, the forest, the traditions, the cultural rituals — these things are what makes us who we are. When we lost that, we lost everything.”

— Mina Susana Setra, the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago, Indonesia.

“Indigenous youths are the future leaders and policymakers. We are doing their part to keep the knowledge alive and language alive, and I think that’s really the face or the picture of what hope is.”

— Monica Ndoen, the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago, Indonesia.

“We hope that society as a whole can rethink its attitudes. Simple, everyday acts can go a long way. Rethink your rampant consumption. Rethink this capitalist way of living — relentless development. We want this philosophy of life to become part of everyday habits.”

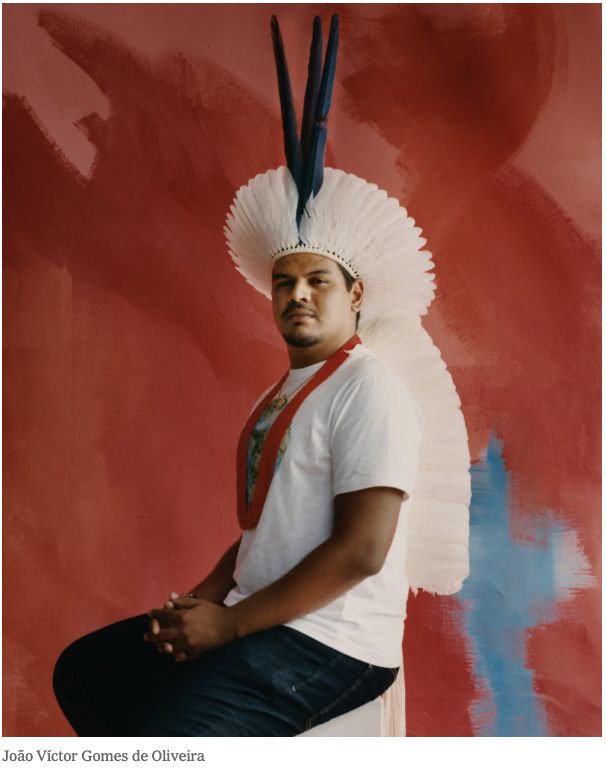

— João Víctor Gomes de Oliveira, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, Brazil.

“We have to re-naturalize ourselves. We have to have more awareness of our actions, more awareness of nature. Unite this divorce that exists between man and humanity and nature. Because what happens to nature, happens to us. It will take its toll on us.

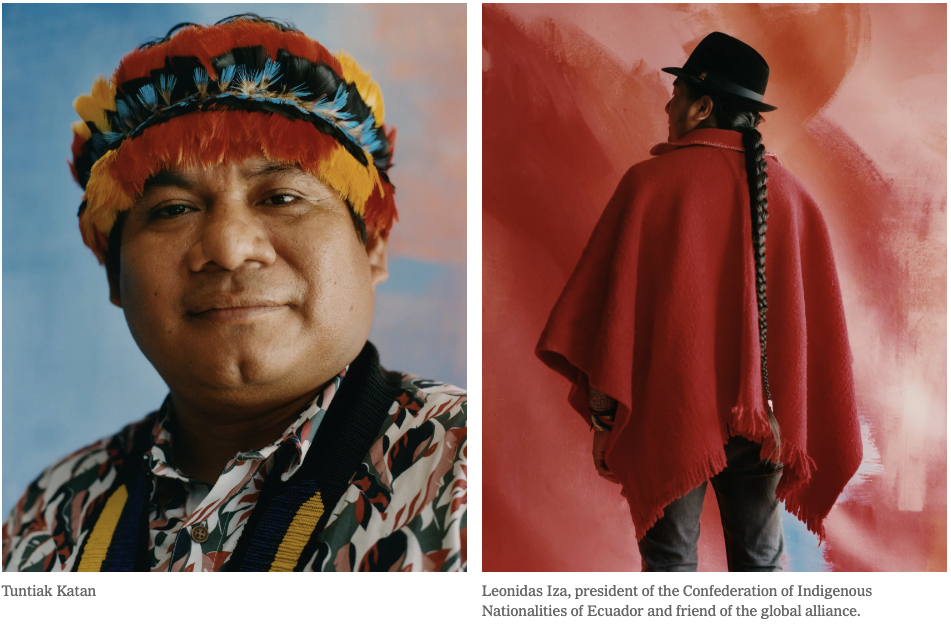

— Tuntiak Katan, Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin, Ecuador.

“My grandparents were forcibly evicted to make way for the construction of a hydroelectric plant. As a result, our relationship with our sacred sites changed, as did our way of highlighting our identity through our language. It’s an example of how a development can destroy the very life of Indigenous peoples. I worry that we are all going to lose the cosmogonic spiritual wealth that we have within our Mother Earth.”

— Sara Omi Casama, the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests, Panama.

“If we don’t preserve our traditional knowledge, it will disappear. We are cultivating intergenerational dialogue to enable our elders to share the knowledge that they have with the younger generations, so we can protect and preserve it for generations to come.”

— Aehshatou Manu, the Network of Indigenous and Local Populations for the Sustainable Management of Forest Ecosystems in Central Africa, Cameroon.

Camila Falquez is a photographer and visual artist living in New York. Isvett Verde is a staff editor in Opinion.