This story has been shared with permission from the Seed and Knowledge Initiative (SKI), one of the Agroecology Fund’s grantee partners based in southern Africa, and has been lightly edited for clarity.

Increasingly, Indigenous knowledge and cultural diversity are being put under pressure as the process of modernization is reaching every corner of Zimbabwe. Rapid changes are taking place in land use practices, farming methods, healthcare, and the cultural ethos and rituals of Indigenous Peoples. Fortunately, in recent years much work has been done by grassroots movements such as members of the ZIMSOFF Central Cluster in Gutu district, to come to a better understanding of Indigenous knowledge and its relevance to sustainable biocultural diversity management. Today, the products of Indigenous knowledge are better understood. Through farmer-to-farmer learning and exchanges, training along these concepts is ongoing.

Through the Nyamandi Agroecology Landscape restoration project, we [SKI] noted that local people often have rich and detailed knowledge of local plants, animals and ecological relations and have derived resources management systems appropriate to their local ecological and social situations. Biocultural diversity conservation or nurturing of resources is management of biological diversity; that is all flora and fauna being very much a part of Indigenous cultures and beliefs. Biodiversity management includes local strategies, institutions, and technologies of farming, herding, hunting, fishing and gathering.

The philosophical understanding of biocultural diversity and ecological land use management

Indigenous knowledge systems

Within farming families and traditional institutions in Gutu district, the Earth is understood to be the source of all that is good. The belief is that local folklore warns of the misfortunes that befall those who fail to respect the Earth, water, wildlife and trees. These values and beliefs are learned from relatives and neighbors as part of childhood experience. They are embedded in the local language, including songs and stories, and reflected in art. The value given to nature is evident in decision-making in all spheres of life. ‘Making a living’ and ‘taking care of things’ are not separated from ‘conservation’, as is the case in the conventional mindsets.

The Indigenous Knowledge System (IKS) is the local community-based knowledge system that is considered unique to the local cultures of smallholder farming families. It is not just a set of information that is in people’s minds, that can simply be recorded and applied. Indigenous knowledge covers a wide range of subjects such as agriculture, livestock rearing, food processing, institutional management, natural resources management, healthcare and others.

IKS is not often documented, but is stored in people’s memories and activities, and expressed in stories, songs, proverbs, dances, myths, beliefs, cultural values, rituals, community laws, local languages, agriculture and technology development.

Culture

Culture is the integrated pattern of knowledge within the farming families, their beliefs and behaviors that consist of language, ideas, beliefs, customs, taboos, codes, institutions, tools, techniques, artifacts, rituals and ceremonies. The development of cultures within these communities depends on the individual family unit’s capacity to learn and to transmit knowledge and practices to succeeding generations.

For the Shona people, the successful evolution and functioning of cultural values and beliefs on biocultural diversity management are anchored by the farming families’ shared values, social rules and systems of conflict management which have local legitimacy.

Cosmovision

The cosmovision of the Gutu district farming families and their traditional institutions includes the perceived relationships between the natural world, the social world and the spiritual world. They refer to cosmovision as the way the local population perceives the world or their cosmos. It describes the roles of the supernatural powers, the way natural processes are taking place, the relationship between human and nature, and it makes explicit the philosophical and scientific premises on the basis of which interventions in nature are made. The words of Headman Mupata below illustrate the Gutu district farming families’ cosmovision:

“Our relationship with the soil is something incredible. The houses that we live in are built from bricks made from the soil. We farm in the soil and the fruits that we eat are from the soil. If we work and get tired, we will rest by sitting or sleeping on the soil. When we die we shall be buried in the soil. We know that soil is something that we should respect, preserve and protect.”

-Headman Mupata

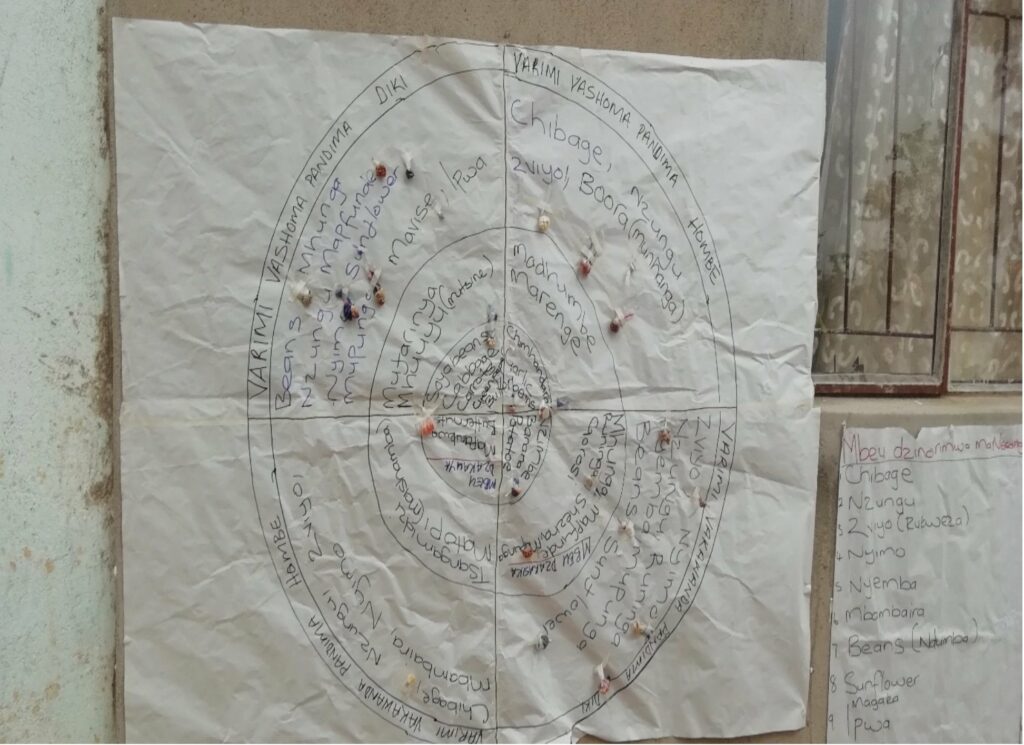

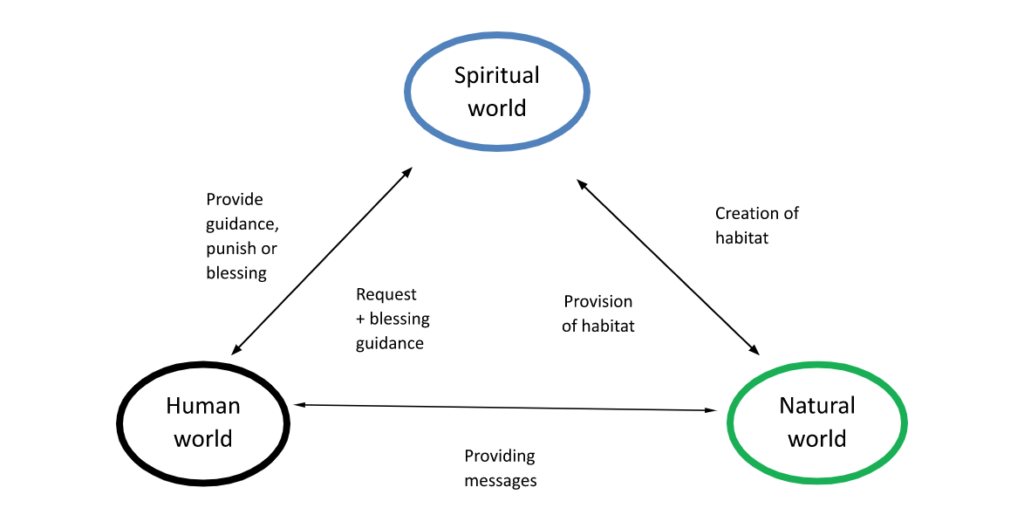

During the dialogues we held with four communities (Mupata, Nesongano, Maungwa and Magombedze) we noted that ceremonies and rituals based on Indigenous spirituality and cosmovision were/are key to the nurturing of natural resources for time immemorial. The art of doing was based on the dynamics of the local people’s wisdom and inspiration. According to the beliefs of the Shona people, the diagram below summarizes how human beings are connected to the spiritual and natural worlds, and how communication is facilitated between the living and the spiritual worlds.

Biocultural diversity conservation

Within the four communities, the values of water, soil, seed and culture are enshrined in biocultural diversity conservation. This is the management of biological diversity that is all flora and fauna being very much a conscious part of Indigenous cultures and beliefs. The belief is that the spiritual world owns both human society and nature because this is where the spirits have their habitat. In order to implement successful biocultural diversity conservation, traditional institutions such as spirit mediums, chiefs, headmen and village heads are supposed to be respected and allowed to play their roles because they are believed to work with the spiritual world.

Key messages on cultural values and beliefs on ecological agriculture

- The land and waters of a group (or coexisting groups) form the meso agro-ecosystem within which their ecological agriculture is practiced. In the agro-ecosystem, we are connected to the soil and water in many ways.

- Kids role-play using soil to build houses and dolls. It is not uncommon to see pregnant women eating anthill soil. We know they say it is a craving caused by iron deficiency, but we think it also shows the value of soil – every living organism is dependent on it.

- This is why the Gutu community says this relationship is just like the one between God and us, because without either, we could not survive. In the Bible, it says that God used the soil to create man – we are, therefore, the soil.

- Water is the blood of the soil that must flow within it, not above it. A living soil should be moist, allowing for the germination of plants, and their growth. Water is also important in our bodies, as well as all other living things that respire or transpire. It is the most unique resource, created with characteristics that are difficult to understand. If boiled, water can change to vapor and disappear as it becomes air. But when cooled in the atmosphere, water can condense to form heavy clouds that can cause heavy rains, with thunder and lightning. These are powerful processes which can result in unpredictable damage and even possible loss of life.

Over 2,000 farming families within the four communities have embraced these values of soil and water to anchor decisions that encompass water harvesting, organic soil fertility management, maintaining wild species and their habitats in some parts of their territory, while altering habitats in other areas to favor the growth of local crops and livestock.

In weighing factors as they make farming decisions, family farmers take into account the nurturing of the soil and water (including the benefits of maintaining the habitats of useful insects). Agroforestry systems (the inclusion of trees in agricultural systems) are common, complex methods that are practiced. Such systems maintain trees among crops, creating successional situations where trees follow crops in a given field, or maintain forest patches separately from fields (where watershed management is a concern). For example, wild species such as edible fruits, herbs and shades are often managed, insofar as their food plants and/or other habitat requirements are maintained within the agro ecosystem.

Practitioners within the four participating communities have developed a communication methodology for local laws and feedback that is leading to the recognition of resource over-exploitation. This methodology was designed in order to organize responses to afforestation or reforestation, water harvesting and soil fertility management. In other cases, the feedback is leading to taboos on the use of species or their exploitation.

While the techniques and tools of biocultural diversity management are easily seen, and some aspects of traditional knowledge are not easily documented, the direct discussion of ‘resource management’ is not usually a productive way to understand local biocultural diversity management. Local people often do not view nature as a bundle of resources; in some cases there may be no translation of the term ‘resources’ in their language. Biocultural diversity management is visible and labeled in local languages. Cultural values that support it are being shared and passed on to younger people through songs, stories, ritual texts and other verbal communications in the local language. When other exotic languages were introduced into local cultures, new values emerged. These new values often do not support the old ways, but focus on increasing the market economy that has a profound indirect influence on local knowledge of conservation of resources through the transformation of non-monetary values into monetary values. This introduced the idea that land, labor and nature are commodities, instead of sacred heritage that binds the members of a community to one another.