This interview was originally published by Agroecology Fund long term partner Alliance for Food Sovereignty Africa (AFSA) for their Voice of AFSA Series and is published here with permission.

Elizabeth Mpofu is a renowned farmer, activist, and global leader in the fight for food sovereignty, agroecology, and rural women’s rights. A practicing organic farmer in Zimbabwe, Elizabeth has dedicated her life to advocating for smallholder farmers, especially women and indigenous communities, ensuring their voices are heard at national, regional, and global levels. She is a founding member and former chairperson of the Zimbabwe Smallholders Organic Farmers Forum (ZIMSOFF), an organization representing 19,000 small-scale farmers—13,000 of whom are women—who practice ecological farming. She has also chaired the Eastern and Southern Africa Small-Scale Farmers Forum (ESAFF) and served on the board of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA). From 2013 to 2021, she served as the General Coordinator of La Via Campesina (LVC), the world’s largest peasant movement.

Elizabeth’s leadership has been widely recognized. In 2016, she was appointed Special Ambassador for Pulses in Africa by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), highlighting her dedication to promoting sustainable, nutritious food systems. In 2017, she founded the African Women’s Collaborative for Healthy Food Systems, bringing together women leaders from across Africa to advance food sovereignty, economic justice, and rural women’s rights. Her work has earned her numerous accolades, including the Inaugural Charlotte Maxeke African Women Leadership Award in 2023 for her outstanding contributions to gender equality and community service.

Early Life and Education

I was born on December 30, 1959, in South Africa, in Barkwana Hospital. My father was working in South Africa at the time, and he married my mother, who was South African.

When I was five years old, my mother decided to move to what was then Rhodesia, before it became Zimbabwe. After we arrived, we settled in a remote area in Manicaland province, where we had our family farm. Although I was very young, I understood that my mother, being South African, was not allowed to work on the farms. So, in the beginning, we had to assist her on the farm since my father had stayed behind in South Africa for work.

It was a big challenge. We had relatives there, but we couldn’t communicate with them well. They had their own homes, and we also wanted to have our own piece of land. However, it was difficult for my mother to acquire land. But through thick and thin, with the assistance of some of my father’s relatives, we eventually managed to get our own piece of land.

I started school when I was six years old at Marume Primary School in Buhera, Manicaland province. One of the biggest challenges I faced at that time was that I couldn’t speak our mother language, Shona. In South Africa, we spoke other languages such as Zulu, Xhosa, a little bit of Afrikaans, and Sotho. But in Buhera, no one was familiar with these languages. So, I had to try communicating in English, but it took me some time to learn and adapt to Shona, which is the main language spoken in Zimbabwe.

I attended school in Manicaland from grade one to grade five. Then, for grades six and seven, my aunt—my father’s sister—took me to her area in the eastern part of Zimbabwe, where I continued my education. However, I was unable to complete my secondary education due to challenges at home. At times, it was difficult for my parents to afford the school fees for my higher education. Additionally, cultural beliefs played a role—at that time, people believed that girls didn’t need to pursue higher education, while boys were considered the most important members of the family when it came to education.

Family Life and Farming Journey

As a girl, I spent much of my time working with my mother on the farm. Although our farming practices were not entirely agroecological, we still tried to work sustainably, using manure and other natural methods.

I grew up in a family of eight—five girls and three boys. Among us, the girls were the majority, and I was the eldest daughter. However, I had two older brothers. Both of them had the opportunity to pursue secondary and higher education—one became a teacher, while the other joined the war to fight for our country. As you know, Zimbabwe has a history of struggle, and my brother was one of the war veterans who fought for our land.

While my brothers pursued their paths, I stayed home with my mother. My sisters also had the opportunity to go to school; they reached secondary level, and one of them became a teacher. Two of my sisters married before I did. Despite not furthering my education, I was happy to be at home with my mother. She taught me so much about farming, and I developed a deep passion for it. She always explained the importance of producing our own food instead of relying on purchases when we had access to land. This is where I truly learned and developed my love for farming.

I got married in 1982 and had three children—two boys and one girl. Now, I have almost eleven grandchildren. Although they live with their parents, I support them, particularly with their education. As a grandmother, I cannot let my grandchildren struggle—I want to ensure they have a bright future. They live in the surrounding area, about 30 kilometers from Chirumhanzu, but they often visit during the holidays. During these visits, we spend time together on the farm.

After retiring, my father returned to Zimbabwe and worked in Harare for a short period. Eventually, he retired fully, but he became ill and passed away, leaving us with our mother. My mother is still alive today—she is now 93 years old. I am currently staying with her in Shurugwi because she is unwell. I am grateful for the opportunity to be with her and take care of her.

The Beginning of My Journey in Environmental and Food Sovereignty Activism

My journey began in the 1990s while my husband was still working as a police officer. At the time, we were living in Masvingo, in a police camp called Zimuto Camp. In this camp, we had a women’s group called Quezon Women’s Club, a club for the wives of police officers. We formed this club to share ideas and work on small projects to sustain ourselves as women instead of relying solely on our husbands.

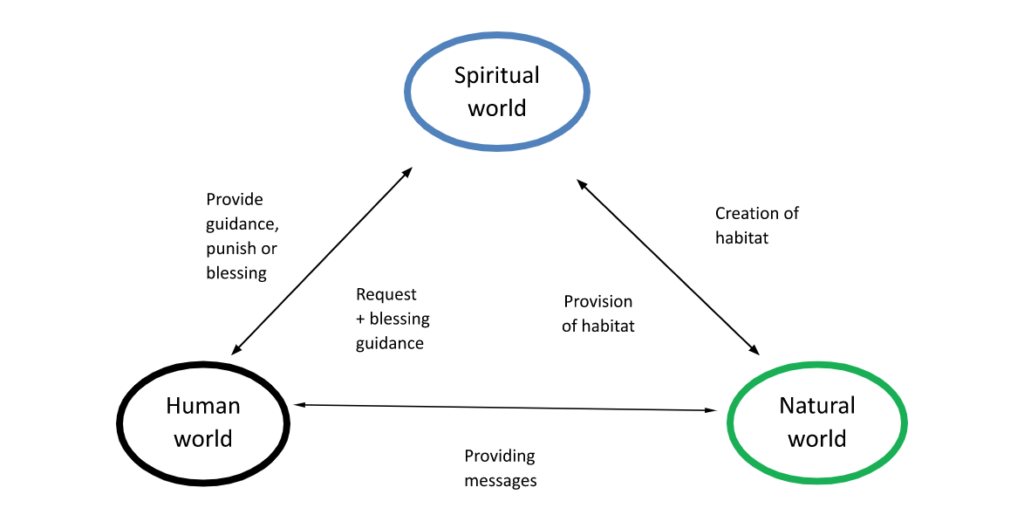

One day, we were approached by three individuals who had identified our women’s club. They were from an organization called the Association of Zimbabwe Traditional Environmental Conservationists (AZTREC). The main objective of this organization was to revive cultural norms and values, particularly traditional farming practices, while promoting environmental conservation and respect for Mother Earth.

During one of their visits, I was chosen to represent our women’s club in this organization. I was approached by Nelson Mdzingwa, Mr. Shamu, and Cosmas Gonese, who was the director and founding member of AZTREC. As I attended their meetings and workshops, I was eventually elected as the chairperson of the organization. AZTREC included spirit mediums, chiefs, war veterans, and ordinary people like myself.

This organization taught me so much—about taking care of the environment, how our ancestors managed soil and natural resources sustainably, and how they produced food without using herbicides, chemicals, or synthetic fertilizers. I was truly happy to be part of AZTREC and to learn from its work.

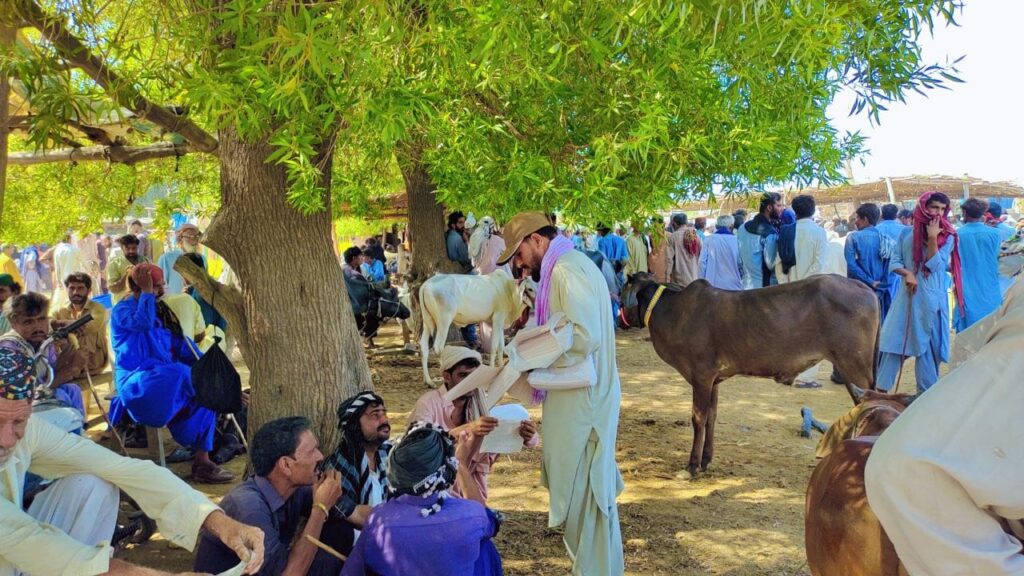

Then, in 2002, during the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, our organization, along with others under the PELUM Association, selected a few farmers to attend. I was among those chosen from AZTREC. At this summit, I learned more about activism. We met farmers from different countries who were also activists, and I started to realize: What we are doing now is activism. We are fighting for our rights, for social justice, and for the environment. That experience deepened my interest and commitment to activism.

As a result, I became involved in the Eastern and Southern Africa Small-Scale Farmers’ Forum (ESAFF), which was formed during this period. When we returned to Zimbabwe, we also established ZIMSOFF (Zimbabwe Small Organic Farmers’ Forum), though at the time, we were not yet registered. Our work was rooted in activism—amplifying the voices of the voiceless, advocating for women’s access to land, and filling the gaps that the government was not addressing.

In 2007, ZIMSOFF officially became a registered organization. By then, our activism had become even stronger, focusing on land rights, sustainable farming, and environmental conservation. I continued to lead ZIMSOFF, and in 2008, I was elected chairperson of ESAFF, a position I held until 2011. From there, I continued leading efforts in Zimbabwe and across the region, strengthening small-scale farmers’ voices in policy and advocacy.

My Involvement in La Via Campesina and Global Activism

In 2011, I stepped down as the chairperson of the Zimbabwe Small Organic Farmers’ Forum because our organization had joined the global peasant movement, La Via Campesina, through the Eastern and Southern Africa region. However, becoming a member of this global movement was a process—it took us two years to complete the necessary procedures and requirements.

During this time, we had the opportunity to host members of La Via Campesina, who visited Zimbabwe from Europe, Asia, and Latin America. They came to see our work even before we were officially recognized as members. When they arrived, they were particularly interested in the discussions around the land reform program, as we were deeply involved in reclaiming land. This marked the beginning of our journey with La Via Campesina.

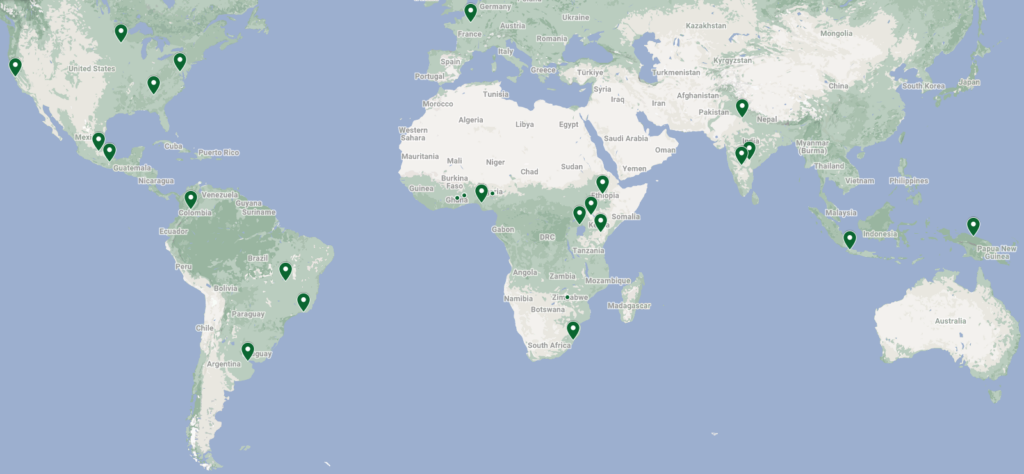

In 2013, I was elected as the General Coordinator of La Via Campesina, representing Africa. This movement is a global peasant movement that fights for food sovereignty, agroecology, and the rights of peasants, including access to land, seeds, and food. I took over the coordination from Indonesia, where the movement had previously been hosted. I served as the General Coordinator from 2013 to 2021, completing my term of office.

During this time, I was also actively involved in advocacy work at the United Nations (UN), especially with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). We represented peasants in high-level meetings across different countries, including Geneva, pushing for the recognition of agroecology and food sovereignty—issues that were not even acknowledged at the UN level at the time.

Through La Via Campesina’s tireless efforts, we played a key role in the development and adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP). I was deeply involved in the process, and I was proud to see this declaration finally adopted in New York. This was a historic moment, as it formally recognized the rights of peasants at an international level. Even after completing my term with La Via Campesina, I remain an active activist because this is my passion—this is who I am.

Our activism gained momentum after attending the World Social Forum, where we were encouraged to create our own independent platforms to amplify the voices of farmers. Before, we had no opportunities to attend international conferences or workshops; the secretariats of our organizations were the ones speaking on our behalf. Yet, we were the ones working on the ground, experiencing the real challenges. This realization pushed us to form our own peasant-led organizations, ensuring that farmers could represent themselves in global discussions.

Reflecting on my journey—from where I started to where I am today—feels incredible. It’s a story I want to share, even with my grandchildren, so they understand the struggles and victories that shaped our movement.

In 2016, I was honored to be nominated as a United Nations Special Ambassador for the International Year of Pulses, representing Africa. This made me reflect on what I wanted to achieve beyond my role in La Via Campesina, knowing that my term would eventually come to an end. As a woman, I also recognized the deep connection between women and seeds—the foundation of food sovereignty.

With this vision in mind, I co-founded the African Women Collaborative for Healthy Food Systems, which I am leading today.

Challenges and Achievements in Advocacy for Food Sovereignty

I will focus primarily on Zimbabwe because we were fortunate when it came to land access and land rights. As you know, we fought hard for our land, and this gave us a significant advantage in our advocacy efforts. We did not face major challenges in engaging with the government because we organized dialogues with parliamentarians and presented our concerns. Many of them were supportive of what we were advocating for—particularly regarding access to land. While Zimbabwe had a land reform program, it did not benefit the majority, especially women and young people.

Our main argument was that women need their own land, and young people also require land to build their futures. Fortunately, this was not a major obstacle in Zimbabwe, as these issues were being addressed. In fact, between 20% to 25% of women in Zimbabwe have received land under their own names. I am also among those women who hold land titles in my own name—not under my husband’s name, but my own. My land certificate is registered in my name.

Even though my husband and I worked together on the farm before he passed away in 2019, he always recognized that this was my land. He also had his own piece of land, and we decided to allocate it to our son. Meanwhile, we stayed and developed our land here in Sherwood, Mvuma (correcting possible misspellings: “Shershe in Mershrigo”). Our goal was always to practice sustainable agriculture.

However, in many other African countries, small-scale farmers, especially women and peasants, still struggle to access land. In some places, men still dominate land ownership, making it difficult for women to secure their own land to cultivate. Many African governments are aware of La Via Campesina and the global peasant movement, but challenges remain.

I remember when we were discussing UNDROP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas) before it was adopted. We engaged with African governments in Geneva and New York, and when the time came for voting, Africa voted as a bloc, with the majority supporting UNDROP. To me, this showed that our governments understand its importance and what it stands for.

However, the main challenge is implementation. Not all African governments have started implementing UNDROP, despite being part of the process. We continue to work together to push for its implementation, ensuring that peasant rights, land access, and food sovereignty are respected and upheld.

Joining AFSA and the Push for Agroecology and Food Sovereignty in Africa

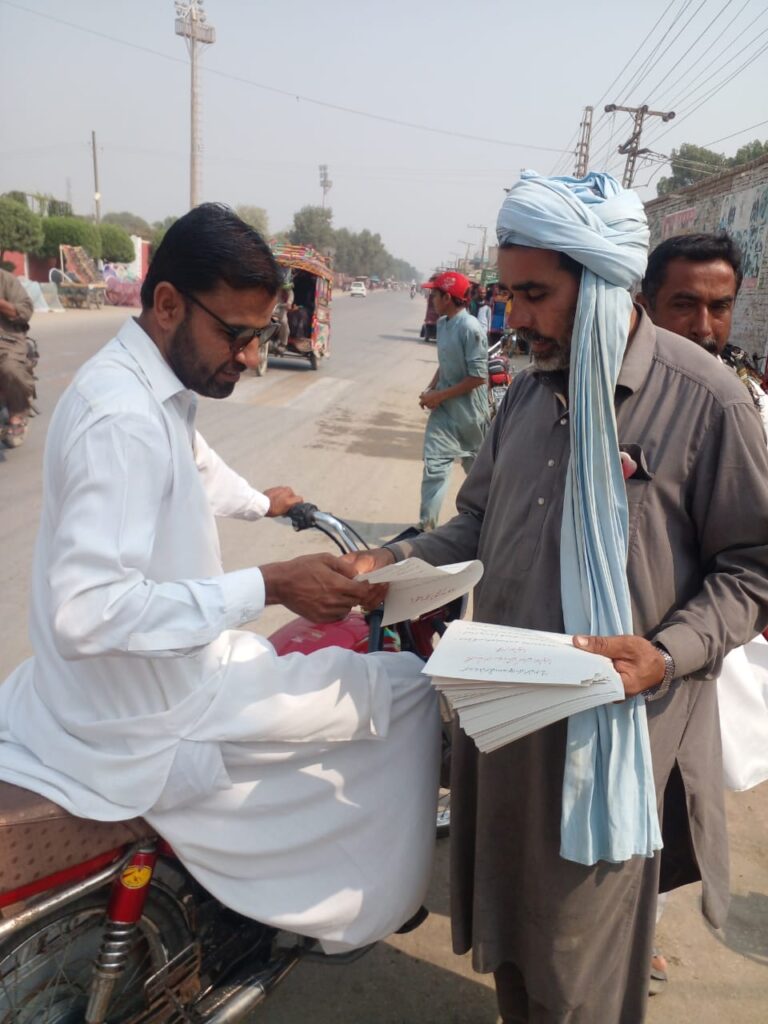

Our path to joining AFSA as an organization was driven by our shared commitment to food and seed sovereignty. As a grassroots organization, ZIMSOFF, which advocates for the rights of smallholder farmers, we saw AFSA as a very important platform that enables us to amplify our voices and collaborate with like-minded organizations across Africa.

ZIMSOFF joined AFSA to strengthen our advocacy efforts on key issues such as farmers’ rights to land and seeds and to promote agroecological practices, which we see as the only solution to climate change.

Through AFSA, we have engaged in campaigns and dialogues to address issues that were not being tackled, particularly the barriers to food sovereignty, while ensuring that smallholder farmers’ voices are heard at national, regional, and international levels. Our membership in AFSA has also allowed us to contribute to and benefit from collective action, especially on climate justice and the rights of women and youth in farming communities.

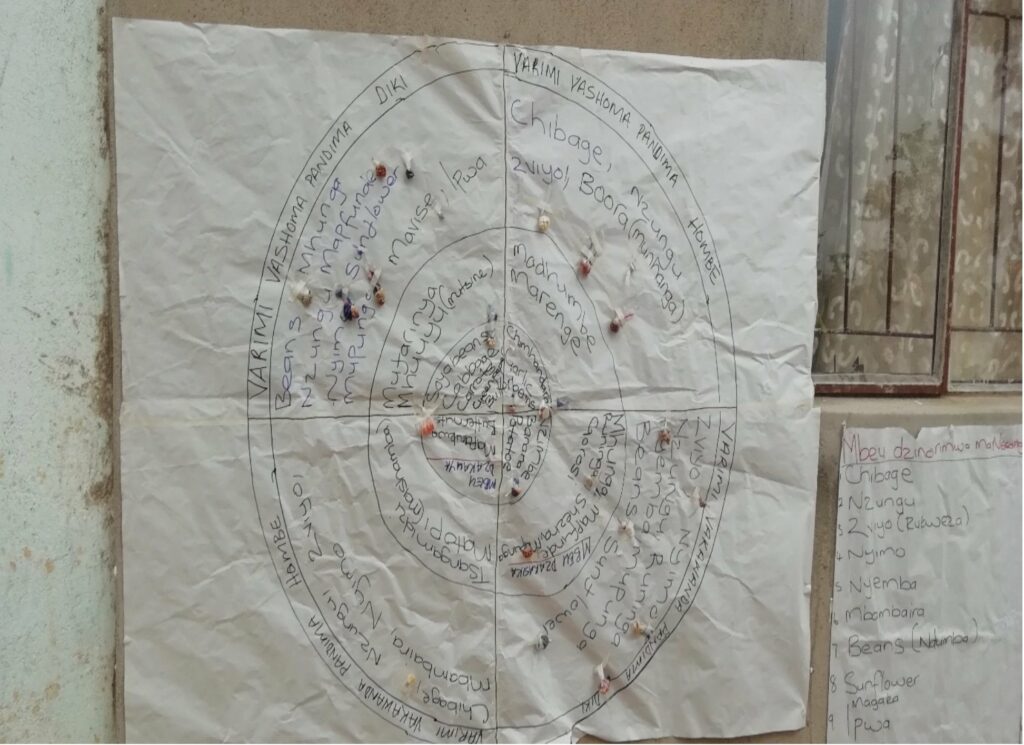

The widespread adoption of agroecology among farmers is about promoting sustainable farming practices that help communities increase their resilience to climate change while enhancing food security and nutrition. We know that these aspects have been lacking because of the industrial farming systems that have been promoted.

We have seen that soils are no longer able to produce enough food due to these industrial systems. This is why we are strongly advocating for agroecological farming across Africa.

One of the key achievements I do not want to leave out is the lobbying of governments—particularly to recognize and support agroecology. Right now, in Zimbabwe, agroecology is in the hands of policymakers. This is very important to us because it shows that grassroots movements can drive systematic change.

I am very proud—proud of myself and of my organization—for the role we have played in empowering farmers to speak for themselves, both nationally and internationally. AFSA has given us the space to amplify the voices of the voiceless, including small-scale farmers, indigenous people, and small fisherfolk.

Being able to engage directly with decision-makers—especially in spaces where we were previously excluded—is a huge accomplishment. This has helped us ensure that our needs and priorities are being addressed. These accomplishments also reflect the power of collective action and the resilience of our farming communities.

Reclaiming the Right to Produce and Decide What We Eat

Food sovereignty is about having the power to decide what we eat and how we produce it. No one should come and tell us, “You must produce maize.” Is maize our staple food? No.

Africa has a diversity of food crops, which our ancestors have been cultivating for generations. But because of colonization, we were made to believe that maize is the only staple food. As a result, we have abandoned our own traditional crops.

But true food sovereignty means embracing our own diverse food crops and rejecting imposed food systems.

Africa Can Feed Itself

I want people to understand something very important about Africa: Africa is a rich and diverse continent, blessed with an abundance of natural resources. We have fertile lands, vast water bodies, and a favorable climate for agriculture.

Yes, we face climate change and systemic inequities, but African agriculture holds immense potential. We must reject the narrative that Africa is hungry. The idea that millions of Africans are hungry is their own narrative—it is not our reality.

The truth is, Africa can feed itself. This is the message I want people outside Africa to understand. And it is a message that our young people must also recognize.

Right now, we are aware of debates about new farming technologies, where people want to introduce IT-based farming solutions. But we know what we want and how we want to produce food.

We are not rejecting technology, but we understand its role. Our youth can use IT and digital tools to help farmers—especially in areas like market access. But we must ensure that technology serves the people, not controls them.

Strengthening Agroecology Movements Across Africa

For agroecology to succeed, civil society organizations in Africa must unite. Many African governments prioritize industrial farming because it serves the interests of multinational corporations.

These governments undermine agroecology and local food systems, even though they know where they come from—they grew up eating food from these very systems. But due to greed, they are allowing multinational corporations to dictate policies.

This is why agroecology movements in Africa must not work in isolation. We must unite under AFSA—not divide ourselves into AFSA West Africa or AFSA Southern Africa. No, we need one AFSA, a strong and unified network that represents us at all levels.

One major challenge is convincing farmers to transition from conventional farming to agroecology. The problem is misinformation, particularly from media houses, which spread the false narrative that agroecology cannot feed the world.

This is a bad narrative, and the media plays a role in reinforcing it because they do not engage with the farmers on the ground. Instead, they promote industrial agriculture without understanding agroecology’s real potential.

To African governments, my message is clear: Work closely with civil society organizations and small-scale farmers. When policies are being formulated, we must be included in the decision-making process. If we are left out, then no one will advocate for agroecology. Many policies are being created without consulting the people who actually produce food. This must change. Governments must engage with farmers at every level. We know what we want. We know how to feed our people. Africa can and must feed itself.

Message to African Youth

Working with young people is a big challenge because many of them want quick money and a quick life.

Through La Via Campesina and many other organizations, we have managed to establish youth platforms where they can have their own space to articulate their issues. We advise them on how to address their challenges, bring their thoughts to the elders, and find solutions together, particularly regarding food production and marketing.

Many young people think that farming is not important, but we try to show them the reality—that food is important for everyone, young and old. Money is on the ground. You cannot just rely on working for someone, thinking, “I will wear a white shirt, a tie, and a jacket.”

No, no, no

Young people must understand that they should work for themselves and create their own jobs. Farming is also a business—you can create jobs in agriculture and earn a lot of money. There are markets waiting for farmers’ products, but if young people refuse to produce, how will they ever have enough resources?

They must work hard, come together, share their challenges, and develop strategies to move forward.

This is the only advice I can give to young people. I know that not all those who have degrees are working. In Africa, we have so many educated young people who are just roaming around without jobs. If we do not build their capacity, advise them, and encourage them to take an interest in farming, then we are failing them as a generation.

I urge all young people in Africa to stand up, work together, and find strategies to fight hunger in Africa. They are the generation we are looking to—the ones who must create a healthy world without hunger or unnecessary challenges.

A message I would like to send to people outside Africa is this: Africa is not just a continent of challenges—Africa is also a continent of solutions.

Farmers across the continent are leading innovative efforts to protect their resources. We are able to feed our communities as Africans, and we are also able to contribute to global sustainability through practices like agroecology.

So, we cannot accept the narrative that Africa cannot feed its people. No.

What I Wish to Be Remembered For

I want people to remember me as a woman who was committed and dedicated—a woman who cared deeply about the well-being of smallholder farmers, women, and young people.

Even now, as I am at home, I continue to work closely with youth and women, educating them about agroecology and sustainability.

I want to be remembered for my commitment to the sustainability of our country and our continent.

The Agroecology Fund is proud to know Elizabeth and to support the inspiring work of African Women’s Collaborative for Healthy Food Systems. If you’re interested in learning more about this work or how to fund this work, reach out to Daniel Moss, Co-Director, at daniel@agroecologyfund.org.