In honor of World Food Day—this year’s FAO World Food Day theme is “Right to Foods for a Better Life and a Better Future—we share an interview with Agroecology Fund grantee partners, Roots for Equity and Pakistan Kissan Mazdoor Tehreek (PKMT), in which we explore their work practicing and promoting agroecology and food sovereignty; demanding just and equitable land distribution; working with small and landless farmers with emphasis on women to build social movements for food sovereignty and climate justice in Pakistan, with a specific focus on their joint campaign against corporate control of dairy and livestock sector.

The Agroecology Fund recognizes that true food systems transformation towards agroecology requires divestment from industrial agriculture. From pesticides to monocultures, deforestation to land grabbing, our fossil fuel dependent food system under corporate control and concentration, is a major contributor to the climate crisis and loss of biodiversity. Roots for Equity and PKMT are not only promoting food sovereignty, but they are also actively working to keep industrial agriculture models from replacing their localized food systems.

Thank you to Azra Sayeed, Founder and Director of Roots for Equity and Wali Haider, Joint Director of Roots for Equity and the secretary of PKMT for sharing their experiences and inspiring efforts in the following Q +A to thwart industrial agriculture from taking hold while there is still an opportunity to do so.

Background

In recent years, the local dairy sector in Pakistan has been facing monitoring by Pure Food Law Authority, Punjab. Milk trucks were being stopped, tests were being carried out for milk contamination, and thousands of liters of milk were being wasted by the authorities. These acts are a threat to the livelihood and food security of small and landless farmers and others associated with the local supply chain. This led to Pakistan Kissan Mazdoor Tehreek (PKMT) and Roots for Equity to investigate the situation. The result was a series of discussions with communities to understand the issue, as well as research to better understand trade liberalization and corporate capture of the livestock and dairy sector to support the launch of an awareness campaign. Learn more about these efforts here.

Q+A

Please share about the impact that industrial agriculture, specifically in the dairy sector, has had on women farmers in Pakistan.

The livestock sector in Pakistan is integral to the lives of nearly 8 million rural families who derive 30-40% of their income from livestock. The sector is particularly critical for small and landless women farmers, with 52% of women working in the agriculture sector engaged in all stages of livestock management; women clean animals’ living space, collect and dry animal manure, make dung cakes, arrange, cut and prepare fodder, feed and milk the animals. Ownership of livestock guarantees household food security, and milk and dung sales are regular and consistent sources of income, even for landless women agricultural workers who have tenuous access to agricultural work.

To date, Pakistan’s livestock sector largely remains in the hands of rural farmers; about 80% of the national milk supply is in the hands of 55 million small and landless farmers with small herd sizes who have conserved local breeds of milk-producing animals that can withstand the regional climate and have adapted to low-resource environments. Additionally, small herd sizes drastically reduce incidences of disease outbreak.

However, women farmers’ role as custodians of livestock and dairy is facing threats from the World Trade Organization that has paved the way for corporate encroachment in the food and agriculture sectors of member countries through legally binding agreements since its very formation.

At the local level, this is giving rise to pro-corporation and anti-farmer government regulations. On one hand, the Government of Pakistan is set on eventually banning the sale of unpasteurized milk through its mandatory pasteurization policy and emerging narratives and policies are targeted towards standardizing and centralizing milk production under the pretext of eliminating adulteration and contamination, as well as to improve productivity and reduce supposed ‘inefficiencies’ in the supply chain – all this means is that acquiring fresh milk from multiple small producers increases costs and cuts down on the profits of corporations. Inevitably, measures aimed at centralization and standardization will wrest control of the sector away from small and landless farmers and replace the current system with large-scale industrial dairy farms.

The full impact of the ban on unpasteurised milk (which is up till now on paper only) is still to be determined. Yet, the women’s comparative experiences in the non-corporate and corporate milk circuits provide important insights into the future.

Livestock ownership and land tenure significantly impact food security and income generation in rural areas. Women agricultural workers raise livestock for various reasons, such as selling cattle, selling milk and dung for daily expenses, or religious and cultural purposes. For the landless, owning livestock is often the only asset they possess. During the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, women could still earn money from milk sales when men’s wage jobs were reduced or lost. Households that owned land and livestock were less likely to experience food insecurity than those that did not. Those with access to land through ownership or leasing had more fodder to give to their livestock, which allowed greater milk yields and the capacity to multiply the herd. Women who own or lease agricultural land, are more food secure than those who don’t have land. Due to the pandemic, milk collectors stopped buying milk from women, but they converted milk into non-perishable dairy items like butter and ghee for their households, staving hunger at the household level.

Women foresee negative impacts on their nutrition intake and income sources following a ban on selling unpasteurised milk. Women livestock keepers sell milk to other households and milk collectors, who then sell it to shops, tea stalls, restaurants, and dairy companies. Women farmers get the highest price for their milk when they sell directly to nearby households, but they prefer selling to milk collectors because they pay monthly. A monthly payment allows them to manage large expenses better. Companies sell processed milk at more than double the amount women are paid for raw milk, but milk collectors and companies refuse to increase the rates paid to women, citing high production costs. A ban on the sale of unpasteurised milk would impact them by denying them the income derived from selling milk, causing financial distress. This would make it unaffordable to keep livestock and access dairy products for household consumption, negatively affecting their nutritional intake. There are no other avenues for alternative work to supplement the earnings of women, especially women landless, agricultural workers.

How did Pakistan Kissan Mazdoor Tehreek (PKMT) and Roots for Equity come to collaborate on this issue? What do you see as the biggest challenges, and which aspects of the campaign have been most successful?

In September 2019, Asia Pacific Women Law and Development (APWLD) initiated the Feminist Participatory Action Research (FPAR) under one of their specific themes ‘Women Interrogating Trade and Corporate Hegemony (WITCH). Pakistan Kissan Mazdoor Tehreek (PKMT) and Roots for Equity as members of APWLD took part in the FPAR, in order to carry out action research with various groups of women in Sahiwal district, Punjab province, who were involved in livestock breeding and caring. Sahiwal district has PKMT membership as well as is home to the Sahiwal cow, a well-known indigenous breed.

PKMT and Roots for Equity participated in the research with a clear intention of exploring the impacts of the Pure Food Law, that the government of Punjab (later followed by all provinces of Pakistan) had initiated, and organizing and mobilizing women farmers/livestock care takers against the corporate capture of the dairy sector.

Based on the series of organizing processes carried out through PKMT, Sahiwal district has a strong women membership. At the national level, a mass mobilization campaign was developed under the title “Save our Invaluable Rural Assets: Campaign against Corporate Control of Dairy and Livestock Sector in Pakistan.” The campaign objectives are to resist the government-imposed regulations on natural pure milk, as well as the increasing trade liberalization and control of the corporations in the sector. The campaign will also build awareness amongst the farming community and the masses to stand up against the attack on their food, livelihood and the environment.

The three-month campaign was carried out from March 8, 2023, International Women’s Day and culminated on June 22, 2023, commemorating the day a brave, peasant woman, Mai Bakhtawar was killed by feudal thugs resisting control over her community harvest in 1948.

The number of activities undertaken through the campaign were as follows:

- National webinars/seminars on agriculture workers, livestock and dairy farmers;

- Social media and print media sharing on the situation of livestock and dairy farmers and impacts of neoliberal policies;

- Theater performances – using art and advocacy;

- Documentary;

- Radio Messages.

Brief details of some of the activities:

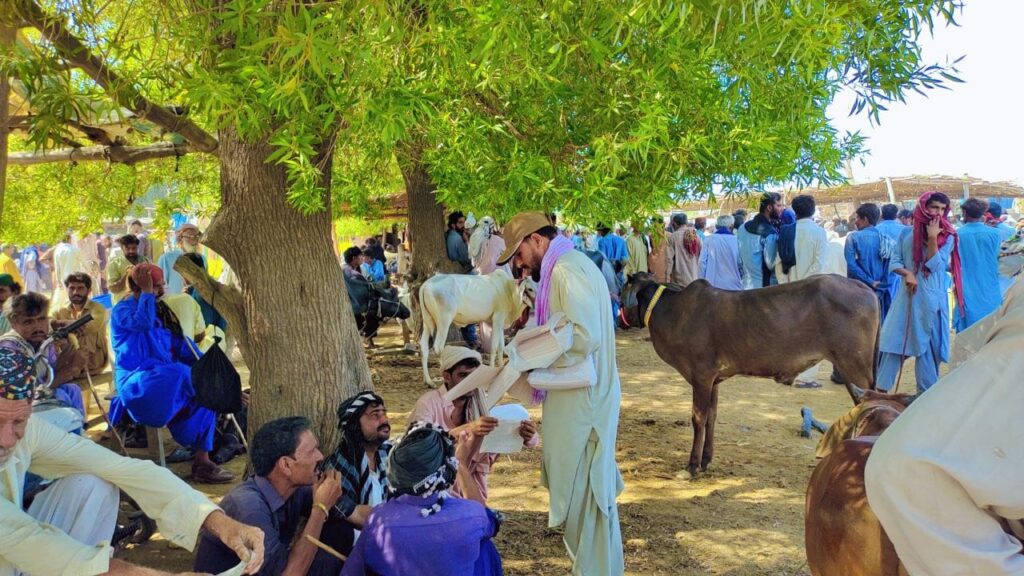

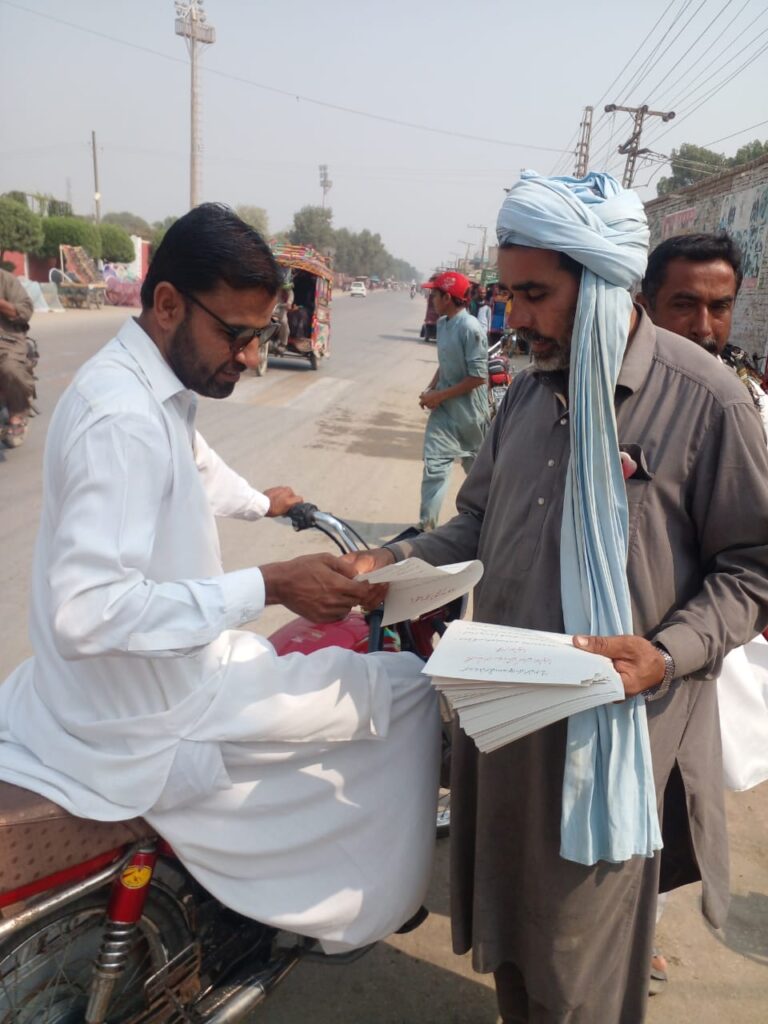

Pamphlet Distribution: The goal was to distribute 500,000 one-page pamphlets developed for popular dissemination across the country. Through the pamphlet distribution we reached on foot more than 500,000 Pakistani citizens in 58 districts of four provinces making them aware of the insidious aims of the Pure Food Laws. These pamphlets were distributed in public places including at cattle markets (mandi), vegetable mandi, local markets, hospitals, railways stations, bus terminals, international days events and at other public points. All distribution was carried out by PKMT members; only in a few districts Roots staff assisted.

Many small town local news channels included coverage of the campaign, reporting on the public’s refusal of Pure Food Laws based on World Trade Organization agreements and the Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures & Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT). A total of 11 Television channels and 15 Newspapers covered the campaign.

Radio Messages: Three short messages of 45, 55 & 60 seconds were developed to highlight the advantages of fresh milk and indigenous breeds of cattle. These were broadcasted daily for three months.The total reach of Multan FM 103, the local station on which they aired, is 16 districts of South Punjab, reaching approx 34.7 million people.

Social Media: Social media has become increasingly important in today’s society, as almost everyone owns a mobile phone. We have shared campaign materials on social media at various times, which highlights how imperialist companies and agents are profiting off our valuable assets and imposing their values on us, while inducing the government to make and implement laws and policies that are allowing not only land grabbing but also eliminating genetic resources based in the plant and animal kingdom, while taking away these resources from small and landless farmers, who are the real custodians of this wealth.

Video Documentary: Save Our Invaluable Rural Assets is the second documentary that PKMT has produced with respect to the corporate capture of our dairy and livestock sector. The documentary demonstrates the critical role of traditional dairy and livestock rearing, as well as the environmental impacts of the industrialized dairy sector.

Though the campaign was successfully able to reach-out to small and landless farmers, the major challenge we face is in mobilizing and organizing fresh-milk sellers (retailers) not just in rural areas but also in the urban small towns. There are two main reasons: i) The enforcement of Pure Food Law in terms of destroying containers of fresh milk through inspection is quite harsh, and hence there is fear of the inspection teams. ii) In many of the districts, law enforcement is not present so people think it is not their issue.

Currently, there is status quo; no major steps have been taken to implement the Pure Food Law. Their declaration that Lahore, the second biggest city of Pakistan, will be made into a pilot project only allowing sale of packaged milk has yet to be acted upon; however the law exists. It is speculated that given that 90% of the milk market is supplied by fresh milk, the dairy corporations are incapable of providing for the huge market. There is also the possibility that the corporations positioned to control the dairy sector sense that they will be challenged by local organizers, and hence are rethinking their strategy. There is still time to ensure small farmers and landless farmers maintain their livelihoods and ways of living.

How will the corporate take-over of dairy in Pakistan negatively impact biodiversity and traditional and Indigenous knowledge?

It is important to mention that since the green revolution in the 1960s, agriculture production has been taken over by the corporate sector. The corporate sector not only dispossessed hundreds of thousands of traditional, local and indigenous seed varieties but also forced the farming community to adopt an unfamiliar agricultural production model which promotes mono-culture, chemical and pesticide and capital-intensive technologies. All of this negatively impacts biodiversity. The green revolution also impacted livestock – hardy oxen that were used for land plowing are now hard to come by, as most of the work is now done by tractors. The use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides has highly impacted small insects, including earthworm, butterflies, honeybees and birds. There is a lack of scientific assessment of the loss; however, visibly many birds, butterflies, beetles are rarely seen in rural areas. Even in the urban areas, the impact on insects and birds is very visible, as they are not seen anymore. The less diverse an ecosystem, the more susceptible it is to climate change.

There are also attempts to take over livestock production with the same false lucrative offer to bring prosperity among livestock breeders. The traditional and indigenous process of livestock production is claimed to be outdated, and a need to promote an industrial livestock production system has been propagated by industrial countries and their corporations. Governments are also buying these ideas like they did for green revolution policies.

“These cows eat five times more than our cows; their cow dung is like water and of no use. Please tell them to keep their cows to themselves, and leave our cows to us.” – A landless woman in Sahiwal, who breeds Sahiwal cows and vehemently opposes breeding of Australian cows such as Holstein Friesian.

Local and foreign corporations are capitalizing on these pro-corporate state policies to capture the dairy and livestock sector, at the cost of small and landless farmers. For instance, in an effort to improve the milk quality and quantity of local herds, the government is encouraging crossbreeding with foreign cattle. Favoring non-indigenous breeds reveals a policy bias towards large scale animal holdings that can only be financed and maintained by large-scale dairy farms. Additionally, imports targeted at corporate dairy farms (e.g. industrial milking systems, genetic material, calf milk replacers, premium fodder) are on the rise. Foreign corporations are increasingly turning towards our markets for supplying these commodities. It is clear that these policies do not recognize small and landless farmers particularly women farmers as key stakeholders and make no efforts to integrate them.

Similar to what we have seen happen with corporate control of plant genetic resources, the control of animal genetic resources technically produces more, but its much less nutritious and costs way more money to produce. The result of cross-breeding livestock is huge animals that give vast quantity of milk daily (40 liters vs 10-15 liters from indigenous breeds) but they are very expensive, need special cool living quarters (not adapted to hot, dry climates), eat at least five times more than traditional breeds, and they cannot walk well due to size. Therefore, they do not graze, and do not breed well. Additionally, their animal dung is watery so is a lost by-product as organic manure. On top of all that, the milk is low on fat and therefore mostly useless. Like the green revolution and GMO seeds – we are seeing lots of food but basically nutrition less, and harmful to the environment and biodiversity.

What is your vision for a food secure and climate resistant future, and how is your work helping to bring that to fruition?

In Pakistan, where feudal structure is so strong, just and equitable land distribution remains the primary solution to world hunger. Small food producers remain as society’s poorest and hungriest class because local elites, big transnational corporations, and imperialist powers continuously take away our lands and plunder our natural resources, exploit our labor, control almost all aspects of food systems, violate our rights, and destroy the environment. In order for us to sustainably produce food for all, we must end feudal control and imperialist exploitation in our own countries by taking back control over land and resources. Currently, according to government data, 5% rich feudal families have control over 64% of land. Under new corporate farming ventures, the provincial governments are providing thousands of acres of land to corporate entities for growing cash and food crops, all destined for export.

Rural peoples directly bear the brunt of climate change impacts, which often translates to loss of lives and livelihoods. But instead of putting the brakes on capitalist profiteering, governments and international institutions are giving the green light to big corporations cashing in on the climate crisis through false climate solutions that will lead to more land grabbing and displacement of rural peoples.

We must shift the future through (1) shifting the bias of policy making toward the peoples’ rights and aspirations, (2) shifting the control over lands and natural resources, and (3) shifting financing toward genuine food systems transformation.

We propose implementation policies that will ensure adoption of agroecology-based production systems— based on autonomy and free from the shackles of agro-chemical corporations. Given the grave looming food insecurity situation, farmers must be provided free access to local indigenous seeds and organic inputs that would allow the country to ensure food security of its people.

In terms of climate justice, again the political framework of food sovereignty and agroecology pave the way for claiming rights over land and productive rights, while also slowly revitalizing and enhancing our genetic resources and protecting biodiversity.

There is an acute need to carry out education including practical application of agroecological methods. There is an acute need for advocacy on the issue and claim government support for agroecology practice.

There is also a need to heighten climate justice campaigns at the local, national, regional and global levels to promote sustainable production and consumption, while sharply de-escalating fossil fuel use but also advocating for lifestyle changes of rich industrial nations and elites of both North and South.

Our work is built on all of the above actions: practice and promotion of agroecology and food sovereignty; demanding just and equitable land distribution; working with small and landless farmers with emphasis on women to build political and social movements for food sovereignty and climate justice.

About Dr. Azra Talat Sayeed:

As an activist with a focus on women’s and peasant rights, Dr. Azra Talat Sayeed has made an important contribution to building peasant movements in Pakistan and in the Asian region. She is the Executive Director of Roots for Equity, a Karachi-based organization working with small and landless peasants, the current Chairperson of the Asia Pacific Research Network (APRN) and the International Women’s Alliance, and a Steering Council member for the People’s Coalition on Food Sovereignty Asia. Learn more about her work in this interview.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter to receive stories like this one about grantee partners directly in your inbox!